Candice Louisa Daquin in conversation with Shruti Sareen

CD: Dear Shruti It is an honor to interview you on behalf of Parcham Literary Magazine. We were fortunate enough to know each other through many mutual projects prior to you writing for Parcham. I have followed and admired your work in The Brown Critique, and Muse India. The obvious question I always ask writers first is –why poetry? Why did you choose to write poetry? What does it exemplify for you?

S.S: Passion brings me to poetry, I think. Being an autistic person, I have very heightened emotional intensity and sensitivity. My therapist would always call me an HSP “highly sensitive person”. Poetry allows me to express this turbulent intensity. It is literally Wordsworthian– a recollection in tranquility of spontaneously overflowing emotions. I have also recently started trying my hand at fiction and creative nonfiction but plot and dialogue of the conventional story structure did not come easily to me, and hence I began with poetry. Perhaps having a poet-teacher who wrote poetry inclined me towards the genre. Another undergrad teacher once said “anyone who is creative and likes words would like poetry”.

CD: What are your views about the increase in the number of women poets, and poets of color, finally having the attention they deserve, after years of poetry being dominated by white men? What can a woman, especially a woman of color, bring to poetry that hasn’t been reflected acutely in our history thus far?

S.S: Women of color is a phrase largely constructed in the West. But surely there is a need to deconstruct the narrative with post-modern feminisms (I speak as a scholar of literature here). The 21st century has seen the rise– in India—of North East poetry, Kashmiri poetry, and Dalit poetry– in English. It was always there in the mother-tongues. So, we definitely need these marginalised voices. Although queerness is slowly getting more mainstream– I want to see more neurodiverse voices and mental health narratives out there. The 21st century has also helped these voices rise, spread and gain recognition through the internet. Women of course add a greater degree of intersectionality to any paradigm and perhaps offer different experiences and perspectives, in some sense.

CD: Many poets speak in euphemisms, as a way to say what they cannot say, in other forms. Is this something you can relate to? Do you appreciate it when you read between the lines in poetry?

S.S: Although my favourite poet Emily Dickinson says “tell all the truth but tell it slant” and my favourite teacher-poet is a big one for slantedness too, I cannot always say that I am in favour of euphemism. Many times, I do like to be bold and clear about what I write, and my metaphors only enhance that, they do not obfuscate it. However yes, euphemisms help when i really cannot say something or if the literal-ness sounds banal and does not belong to poetic language– though mostly I go all out and take crazy risks in saying what I have to say.

CD: You presented a paper on “Food, Love and Self in Indian Women’s Poetry in English.” A few years ago. What inspired you in terms of that subject, to relate food and love and self in terms of poetry and specifically, women’s poetry?

S.S: Ah, that paper has garnered a lot of attention, I don’t know why, and Sophia College, Mumbai University has actually prescribed it in their undergraduate syllabus. Mostly these days I puzzle my head over food production and consumption with regard to vegetarian and non-vegetarian food, but yeah I do realise food does psychologically mean something more than just putting something edible inside ourselves. That paper tried to see food as a marker of identity at three levels: the bodily personal and individual level, the interpersonal level as a mode of offering love, and collective identity as a community.

CD: Michel Foucault wrote “I don’t write a book so that it will be the final word; I write a book so that other books are possible.” When you think of this, how do you relate or not relate to this conception of what writing and its outcome embody?

S.S: That’s a good point. As far as my writing is concerned, I would again fall back on my autism diagnosis. I do write so that other books are possible– so that more neurodivergent voices come out, more intersectionally queer voices come out, so that others too gather the courage to voice their traumas authentically– familial, sexual, or otherwise. In India and south Asia, at least, there is great need of that.

CD: Talk to me about what it is like to be a woman in India in terms of equality? Women in the West are still not equal; their rights are constantly eroded. We are woefully ignorant of the real-lived-experience of women in India. How do you see it in 2025?

S.S: In a larger societal sense, women are surely still unequal. However, looking at intersectional realities is a must. As part of my PhD, I looked at Dalit women’s realities, North-East and Kashmiri women in conflict, poor women, queer women– as reflected in poetry. Currently I work as Research Assistant on a project pertaining to Muga silk of Assam, a state in north-east India. There too, we are specifically looking separately at the role and the problems of women rearers and women weavers. Coming personally too myself– of course I have faced street harassment (which woman hasn’t?) and even molestation by a landlord and my childhood tabla teacher– and I see it operating in spaces such as banks and sometimes in the family as well– however largely that hasn’t been the biggest cause of my marginalisation and discrimination. Also, I feel a little weird talking of this because I myself have been accused of unintentional autistic stalking, so I have had occasion in life to see myself as a victim and perpetrator both.

CD: You have quoted on social media the beautiful words of Anna Akhmatova, where she says: “All that I am, hangs by a thread.” How do you relate to this quote in terms of how you see your place in the world and its place in you?

S.S: This is a deeply personal question. “All that I am, hangs by a thread” indeed. This was put up as my Facebook cover picture in the context of being continuously suicidal for two years now. I was an undiagnosed autistic child who saw her parents getting divorced and into second marriages in my middle school and high school years. At the same time, I fell in love with a school teacher. Later falling obsessively autistically in never-ending oedipal love with a college teacher made me confront– first the issue of queer sexuality, then accusations of stalking, then decade plus long depression, then autism, then institutional repercussions over time led to the question of where is home? Of losing (?) a home I had found, that I was not ready to lose. Questions of home, identity, attachment having reached an extreme head, I have reached the intersection and the extremity of all issues that have haunted me all my life– and hence my current condition, and hence the quote.

CD: What do you think about the concept of ‘golden years’ especially in relation to happiness and innocence found at school/college and do you think this is s subject that is repeatedly revisited in writing in general? How much does it impact your writing?

S.S: What a question! It may or may not inform writing in general, it certainly has come to impact my writing a great deal as it is connected to questions of home and trauma, of growing and finding myself, and of finding what has come to be the love of my life, even if it’s unrequited. Growing up in a conflicted house, I would say school and college have been spaces of home for me. I was extremely attached to my school. I was a very shy kid in school, typically autistic. I wasn’t good at math, at sports, and some science subjects. School offered opportunities but perhaps not the ones I needed. In college, my main subject was literature. In college, I lost my shyness and became much more outgoing and outspoken. I gained acceptance, and I was even the editor of the college magazine in my final year– a part of the students’ union. College became home, although initially it took me a few months to “belong” there. If I search for home, for stability in the college… As I told a friend, it may be an illusion but it is all I have.

CD: How does nostalgia play in terms of what inspires you write, what subject(s) you choose to write about and how it informs your emotional stance when writing?

S.S: That’s an interesting question. A lot of my writing takes my own past (and current!) life as material. Again, falling back on Virginia Woolf, she says the past can be better understood only in the present, not while it is actually happening. My novel The Yellow Wall is very autobiographical and nostalgia may certainly be seen as playing a role there. As there is some distance from my past self, there is greater self-awareness and a sense of self examination. These inform the book as keenly as nostalgia does– or I hope they do. It’s a common concept in literature while talking of autobiography– the difference or the distance between the writing self and the written self.

CD: India is a fascinating country of extremes. The middle and upper classes seem to receive finer educations than anywhere in the world, whilst many of the working poor and lower class and caste do not have access to this degree of education. What is your stance on this?

S.S: Do we have finer education in India than anywhere in the world? I don’t think so. Sadly, education in India, as elsewhere, is a domain for the privileged. With right wing ascendancy and increase in privatisation, with the replacement of UGC grants with HEFA loans and so many other things happening in higher education in India right now– education is going to be bought by money, not earned by merit in the coming years. The divide between rich and poor is going to be cemented by this. Caste reservations will decline unless private institutions implement them as well. It is a sad and dismal future that stares us in the face.

CD: What role does trauma have in the struggle to write? Many writers seem to suffer physical or mental issues, that challenge them in their personal and daily lives. Have you found that there is an upside to this? In that trauma can be released through writing?

S.S: Both my novel The Yellow Wall and my speculative short fiction manuscript Berserk Banshees were envisioned due to extreme crises in college. My love letters (work in progress) Sapphic Epistles are being written as a pathway to healing and recovery, to address my conditions of mental breakdown. And poetry, doesn’t that always come from a passionate tumult… recollected in tranquility, as the quotation goes? Even my academic research projects are envisioned based on my conflicts and traumas.

I use this Hindi word a lot “vyakt“. It means to voice, to express. Voicing and expressing my traumas is the whistle of the steam engine, the spouting of the volcano, so yes certainly, writing helps me reach out to the world and convey my own truth and experience in so many ways. It has become my prime mission in life.

CD: What role does shame have in terms of inhibiting a writer? Especially a female writer, or do you think it’s not gender dependent?

S.S: It might be gender-dependent for many. But in my case, it was my personality arising from a mixture of autism and trauma for which I was primarily shamed. It is deeply humiliating especially when one is already in trauma. I was always the younger one, the “subordinate” one, without a regular job or societal position to protect me so it was easier for people to do that.

CD: You have said a few times, you do not feel you fit in with others. Can you describe how this impacts what you choose to write and whether that has been beneficial in some ways, to be more singular minded than joining the crowd? The idea of the black sheep is a theme that comes up a lot in poetry, why do you think this is?

S.S: I don’t know. I do feel different in many many ways, a misfit. I think autism and mental health issues are deeply misunderstood in our society and ignorance and misconceptions abound. Some knowledge is still there now about caste and queerness– limited social acceptance– but not about this. My writing is very heavily influenced by it as I mostly write from my experience. Although yes, I am happy and proud of my identity and it’s also the source of whatever strengths I have, yet I find it deeply difficult and traumatising to live this life that I have been given. So, it’s difficult for me to say. Sometimes at my worst and lowest, I wish I wasn’t like this simply because it would have got me better acceptance in society. Of course, I wouldn’t have my writing either or my academic research plans in the pipeline, but then I wouldn’t have any conflicts with the woman, with the place—and what wouldn’t I give for that! The same teacher I fell in love with had told me long ago when I was friendly with her that “you’re not as different from others as you think. And if you are, it’s your individuality and it’s the most precious thing you can have.” So, she gave me the biggest validation I craved, but I don’t know what to think now. Would she say the same today when she has been so traumatised by me?

CD: What do you make of the toxic-positivity in writing and does it nullify writing because of its emphasis on writing being up-beat, which is limiting the writer’s ability to be open about how they feel?

S.S: I intensely, passionately, honestly and authentically feel all my emotions— “even when I feel nothing, I feel it intensely”- I’m quite like Plath that way, and this is why this culture of toxic positivity is clearly toxic and lethal for me. Poisonous. People are scared of feeling their emotions, they want to shy away, live in denial, make happiness the only emotion we are allowed to feel instead of being real and authentic and “ourselves”, the way Virginia Woolf would tell you to be. Individuality and authenticity are not valued. People want writing to be glamourous, getting awards prizes publications and honours, without the pain and the messy business of living.

CD: Many mental health movements today are asking people to reconsider the old bigotry surrounding depression and mental illness; that it’s a choice, or a sign of someone being lazy or weak. The opposite is true. People with mental illnesses are often very strong, because it takes great strength to endure it. Especially when others do not help and there are few resources. We are living in a world where more and more people struggle with mental illness and judging them or shaming them only makes it more unbearable for them. Do you think this is why poetry has had a resurgence? Because it’s not as judgmental and it is a way, we can express ourselves without being shamed? Do you find strength in poetry for this reason?

S.S: Thank you for asking this question. Yes, it is infuriating. It is true that there are very few good or affordable resources and hardly any people who are kind or willing to help. That is why I want to at least try to convey my truth or experience in this life. I always had problems with normative conceptions of weak and strong– people say crying is weak (Charlotte Bronte would differ), being too attached to another is weak. Anyway, I never believed in all these normative value-judgements. Some teacher once said I am giving a “bad name to autism”– thing is, they don’t really know what is autism. If you know one autistic person, you don’t know them all. Secondly, my autism is compounded with trauma, but one needs eyes to see and ears to hear to recognise that. Thankfully there are some people who do “see” the pain too, not always maybe, but hopefully sometimes– and my writing is forever an attempt to express it.

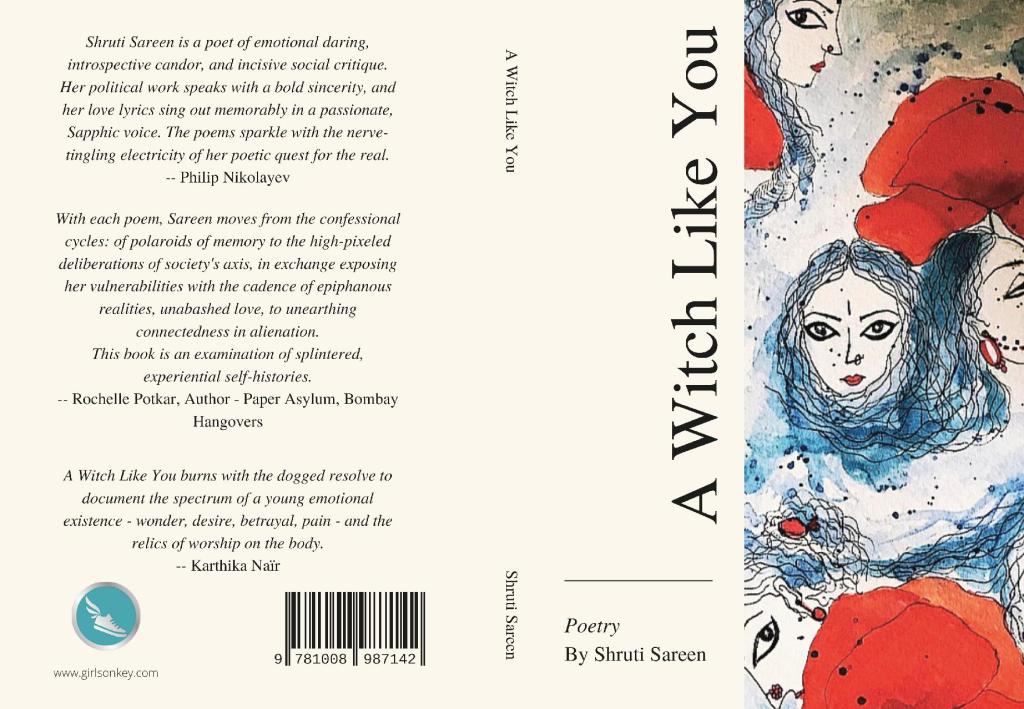

CD: With your debut poetry book A Witch Like You, what were your intentions with the book? What key things were important to convey?

S.S: Thank you! As my preface or introduction to the book explains, the title is actually an ambiguous one, meant to convey simultaneous feelings of intense love and intense pain. The ambiguity which I convey in a text message by calling the woman a “devi goddess” and a “stupid woman” in the very same sentence. So, you know, good witches, bad witches. But at its core, it’s about being bewitched by someone and being utterly devoted to this magical being. Most of the poems in that book follow this trajectory of exploratory falling in love, entrancement, deep devotion, loss, pain, and an attempt to find some sort of release, although there are 3 interludes of nature poems, everyday life/object poems, and political poems.

CD: What importance have you put on writing-groups as a means of encouraging writing? I read a few days ago that Susan Sontag felt writing in isolation was the true way to get to the core of writing. I am more productive in isolation but I appreciate that for many, writing in a collective really helps them. Where do you fit in that?

S.S: Individual, definitely. I like to execute and control my own ideas, and I’m not a fan of group writing or collaborations. We can do different parts of a book, or one does the research the other the writing. Something like that. The two parts should be distinct and demarcated. Of course, if two people have a conversation in poetry like a duet, that can be beautiful.

CD: Tell us about what is coming up for you in terms of future projects and what you are interested in?

S.S: My hugely long novel, The Yellow Wall, is forthcoming from Queer Ink publishers, Mumbai. My manuscript of short speculative fiction Berserk Banshees (of novella length) is complete and currently submitted to publishers. My love-letters to creatives- artists writers poets actors singers– Sapphic Epistles, are in progress but a lot of research needs to be done for it. I had a novella in my head– based partly in saturn and partly on an imaginary island on the river Brahmaputra in Assam. But it’s in my dreams only, as of now. Poetry continues in interstices— when I have enough many, I will think of compiling a second collection. I already have a title for it, I think!

CD: Thank you so much for answering these questions. We at Parcham are so fortunate to have your accomplished and beautiful work in our issues. We hope to work with you again.

Shruti Sareen, graduated in English from Indraprastha College for Women, University of Delhi and later earned a PhD from the same university, titled “Indian Feminisms in the 21st Century: Women’s Poetry in English” based on which two monographs from Routledge are forthcoming. Her debut poetry collection, A Witch Like You, was published by Girls on Key Poetry (Australia) in 2021. Her autobiographical novel The Yellow Wall is forthcoming from Queer Ink Publishers, Mumbai. She is working on a series of love-letters addressed to creative artists and figures mainly on themes of mental health and sexuality, Sapphic Epistles, and her collection of speculative fiction around similar themes, Berserk Banshees has been submitted to publishers. She was an invited poet at global poetry festival, hosted by Russia, Poeisia-21. Her current academic research interests mainly centre around neurodiversity, trauma and sexuality in the lives of creative artists and figures, and place and memory. Most recently, she has been a Research Assistant at Gargi College, DU with a short-term ICSSR project on the muga silk of assam—the state which fascinates her so very much.

Leave a comment