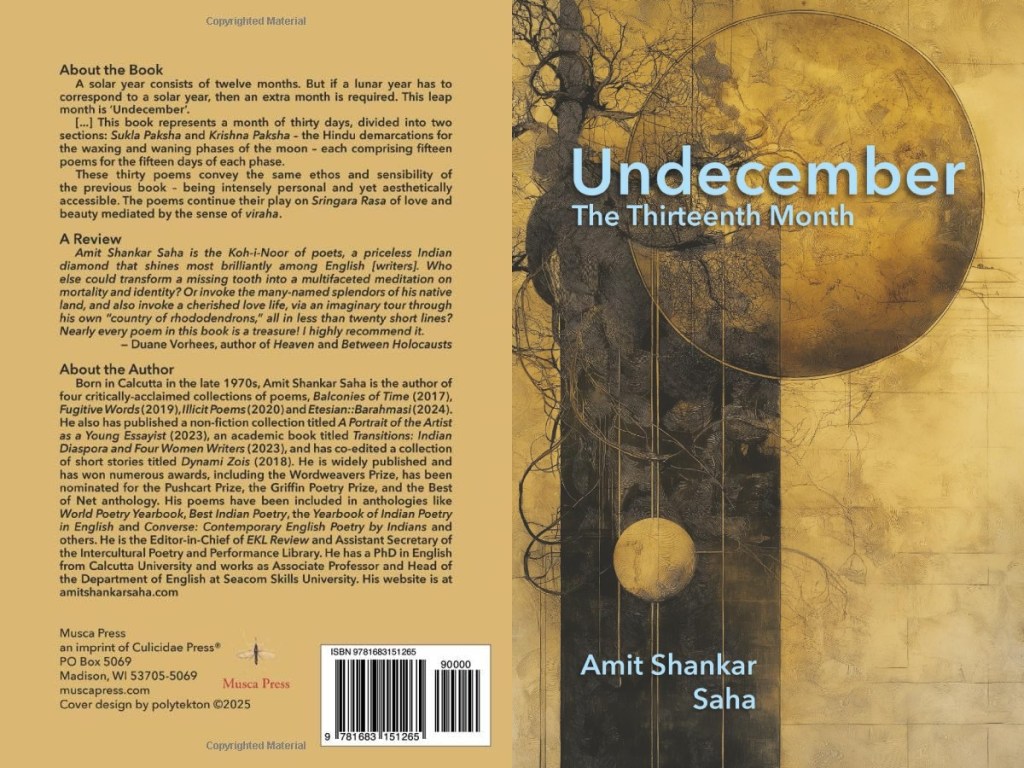

Review of Amit Shankar Saha’s Undecember: The Thirteenth Month

Reviewed by Subashish Bhattacharjee

In Undecember: The Thirteenth Month, Amit Shankar Saha extends the calendrical imagination that shaped his earlier volume, Etesian::Barahmasi, into a liminal poetic space: an intercalary month, a surplus of time composed of “stolen days.” Conceived as the lunar adjustment that reconciles discrepancy, “Undecember” becomes both metaphor and method—a temporal annex where what could not be accommodated earlier now finds form. Structurally divided into Shukla Paksha and Krishna Paksha, the waxing and waning lunar phases, the collection arranges thirty poems into a symbolic month, aligning personal affect with cosmological rhythm.

At its core, this is a book of viraha—of separation as both wound and generative principle. Saha states in his preface that the poems continue to explore Sringara Rasa mediated through absence, and the thematic consistency is unmistakable. The beloved appears as memory, distance, technological mediation (video calls, photographs, devices), and geographical disjunction. The lyric voice repeatedly returns to trains, telescopes, beaches, temples, hills

—sites that promise convergence yet deliver deferment. In this sense, the “thirteenth month” is not merely extra time but deferred time: a space of emotional afterlife.

The opening poem, “Undecember,” establishes the collection’s governing metaphor: the speaker steals “days from dreamy weeks” to construct a month that “levitates out of sight.” This image of levitation recurs throughout the book, often associated with fleeting intimacy or imagined reunion. Time in these poems is elastic, subject to both astronomical and emotional physics. References to “Doppler Effect,” “Total Internal Reflection,” “Mitigating Mathematics,” and “Units of Forgetting” suggest an effort to intellectualise longing—to translate affect into quasi-scientific lexicons. The result is a distinctive idiom where physics and metaphysics intersect.

Indeed, one of the more interesting features of the collection is its recurrent scientific vocabulary. In “Total Internal Reflection,” the movement of the gaze between “you” and “me” becomes an optical problem; in “A Syntax Error,” the world’s “code” refuses to compile; in “The World of Vestigial Organs,” love is figured as “a cyborg / in a world of organs / turning vestigial.” These metaphors gesture toward a contemporary consciousness, alert to technology and digitality. They also situate Saha’s lyricism within a

twenty-first century sensibility, where longing must coexist with devices, networks, and mediated presence.

At the same time, the collection remains rooted in culturally specific landscapes. “Footprints in Water” invokes the Sarayu; “Missing You in Konark” situates desire against the backdrop of the Sun Temple and Chandrabhaga beach; “Rhododendrons” travels imaginatively through Baijnath, Munsiyari, Mukteshwar, Nainital. These are not merely touristic references but mnemonic anchors. Geography becomes affective cartography. The beloved is distributed across hills, ghats, and seas. Such poems participate in a long Indian lyric tradition where landscape mirrors interiority—recalling, albeit in contemporary diction, the nayaka–nayika dynamics of classical poetics.

The book’s tonal register is largely gentle, contemplative, and accessible. Saha favours short lines, conversational syntax, and a relatively transparent diction. The poems seldom strive for opacity. Instead, they articulate emotion in direct, sometimes declarative statements: “If I don’t love you much / the world will be much worse.” This stylistic clarity has a double effect. On the one hand, it makes the poems approachable, aligning them with a broad readership and with the increasingly popular mode of social-media-inflected lyric. On the other, it occasionally risks reducing complexity to statement. Where the metaphors surprise— “distance freezes / time like a chunk of ice” —the poems gather resonance; where they lean toward assertion, they sometimes settle too quickly into paraphrasable sentiment.

The twin poems “The Missing Tooth” and “Denture” exemplify both the strengths and limitations of Saha’s method. The extraction of a tooth becomes an emblem of aging, loss, and existential diminishment. The body’s attrition mirrors emotional insecurity. The conceit is extended with wit—“Till then let us rinse our mouth verbally / for we always maintained oral hygiene”

—yet the emotional arc is spelled out with little ambiguity. The poems succeed in humanising vulnerability, though they rarely leave interpretive gaps for the reader to inhabit.

The second half of the collection (Krishna Paksha) grows marginally darker and more speculative. “Silence of the Sleet” imagines a dystopian world in which the lovers are the last beings alive, communicating across deserts of ice and sand. “A Slow Stirring Surface” stages boredom as a companion in absence. Here the repetition of “Boredom and I sit together” enacts stasis formally. These poems gesture toward existential solitude beyond romantic separation. Yet even here, the central axis remains relational.

One of the more compelling pieces, “Units of Forgetting,” contemplates memory from a cosmic vantage point. The speeding train appears static from galactic distance; change is perceptible only at proximity. Forgetting becomes a measurable unit, though paradoxically immeasurable in lived experience. This oscillation between macrocosm and microcosm—between galaxies and rooms, beaches and beds—gives the collection a structural coherence. The lunar division of the book reinforces this rhythm of waxing and waning presence.

Saha’s intertextual gestures are discreet but suggestive. The reference to a song of “Gurudev” (“Tomaro ashime prano mono loye”) evokes the legacy of Rabindranath Tagore, positioning the beloved within a lineage of devotional lyricism. The final poem’s image of a girl dreaming of speaking to Jacques Derrida in French introduces a playful philosophical note, hinting at the author’s academic milieu. Such moments subtly frame the collection within both Bengali and global intellectual traditions.

If one were to situate Undecember comparatively, it might be placed alongside contemporary Indian English lyric that privileges intimacy over overt political engagement. Unlike more stridently interventionist poetry, Saha’s work turns inward. The political appears obliquely—through ecological metaphors (“Ecology of Love”), carbon footprints, and dystopian speculation—but it does not dominate. The emphasis remains on the phenomenology of missing, on the ethics of attention to another.

The book’s strength lies in its sustained mood. It creates a continuous emotional climate—a gentle winter of recollection—rather than dramatic crescendos. Readers seeking radical formal experimentation may find the terrain familiar. Yet familiarity here is also part of the design. The thirteenth month is not a rupture but an extension, a supplementary chamber where echoes reverberate.

Undecember is less about the novelty of its conceit than about the persistence of its longing. The poems return, again and again, to the fragile hope that distance can be traversed—if not physically, then imaginatively. The lunar cycle assures recurrence; waxing follows waning. In this cyclical temporality, separation is never absolute, only phased. Saha’s collection inhabits that interstice between presence and absence with sincerity and quiet craft, offering readers a calendar not of days but of remembered breaths.

Subashish Bhattacharjee is an Assistant Professor of English at Munshi Premchand Mahavidyalaya. His doctoral research, from the Centre for English Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, focused on the intersections between the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, STEM Humanities, architectural philosophy and urbanism, and new media. He has held fellowship and visiting positions at the University of North Bengal, Jawaharlal Nehru University, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, KU Leuven, and Goethe Universität Frankfurt. He has been an editor of the journals, The Apollonian, and Muse India. His recent books include The City Speaks (Routledge), Japanese Horror Cultures (Lexington), Horror and Philosophy (McFarland), and the forthcoming Reiterating the City (Bloomsbury), David Cronenberg: ReFocus International Directors (Edinburgh University Press) and Miike, Shimizu, Nakata: Japanese Cinema Beyond the Norm (Peter Lang) among others.

Leave a comment