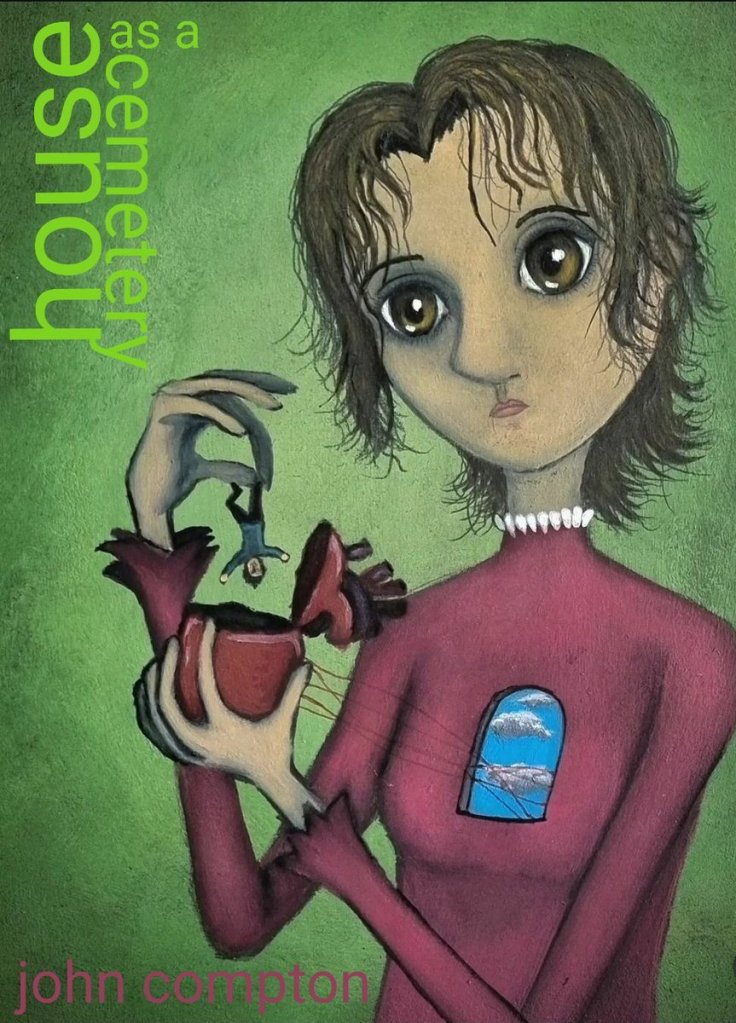

Name of the Book: house as a cemetery

Author: John Compton

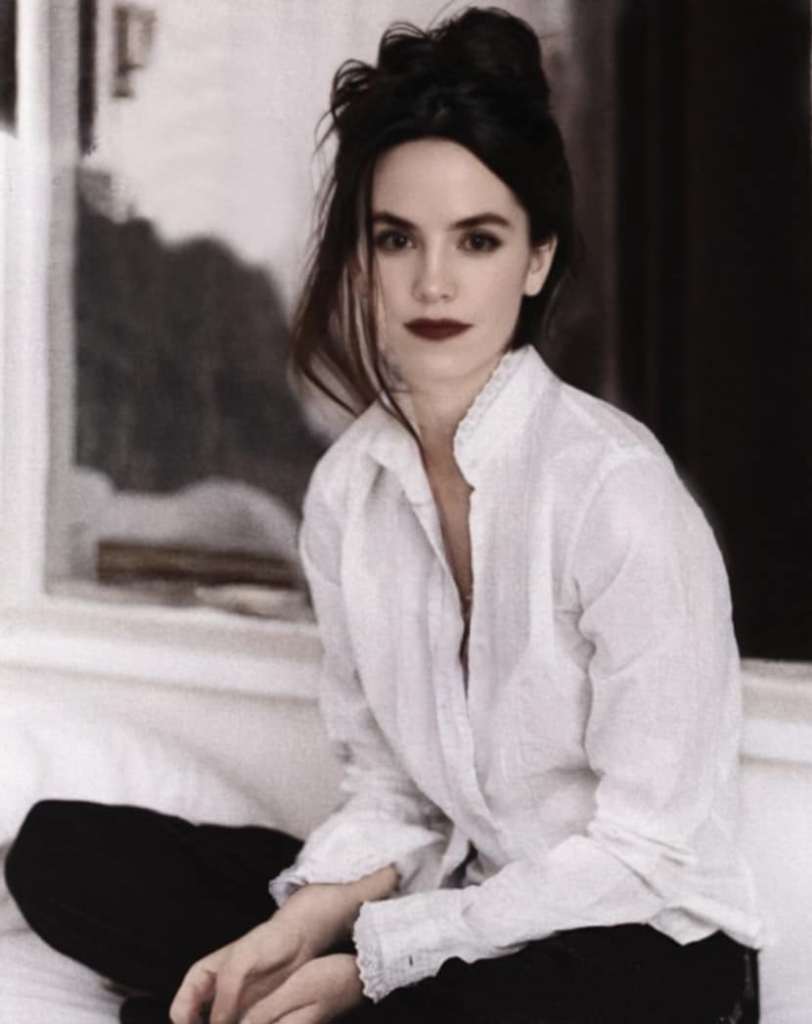

Review by : Candice Louisa Daquin

It is apparent, from just seeing the titles in the table of contents, John Compton is going to smack us with a high wattage battery of poems in his unable-to-replicate style, examining death, grief, queer-identity, and the human experience amidst loss and societal indifference in his latest collection house as a cemetery. From the first section title called: the calling hour & an exposition of the dead, Compton’s a hard act to follow; his writing writhes with the awareness of social injustice and division, in a gloves-off style that peals layers of your skin, in its refusal to go quietly. This intensity is no better located than in the poem my mental breakdown at a greyhound station, where Compton’s raging, unrepentant imagery is dwarfed by the momentum of the subject-matter and then forced to shine a light where we usually avoid looking:

the stagnating water

has a dreadful calm.

a sadness blooms

like ick: gill maggots

You are not safe reading Compton, you are asked to be more than passive reader, you are asked to understand how things really work. His writing whilst deeply personal, possesses such sore-throated immediacy and intensity that you can only really appreciate him by reading him. In the 4th section: blacked out borderland from an exponential crisis, Compton masterfully reduces the message (and in so, magnifies it) by a series of similarly laid-out, short prose-poems which tight attention to pain’s center:

i’ll grow something once i’ve

died the splinter now a part of me like

blood it fastens to my body like a bone &

to remove it causes sadness but also

pleasure

Worth noting, everything is intentional; like Bukowski, Compton’s awareness of language and its impact, as well as how to produce seemingly-simple lines that bulge with deeper meaning, appears innate rather than something learned over time. Thus, the surrealist nature of Compton’s writing (and mind) isn’t over-conscious so much as fluidly part of his psyche. This enables the reader to latch onto his stream-of-consciousness in symbiotic journey through the key themes in Compton’s writing:

even when the mouth is

closed you touch the small hands &

fit them inside yours electric surges through

the both of you like a bulb

Some readers may baulk at the phantasmagoric surrealism in Compton’s (seemingly) untitled, less obvious work(s) but for lovers of poetry and words, how could you not collapse into the visual feast of his linguistic arrangements? It’s a bit like hearing a song in a language you don’t know, can you still appreciate the music? Still dance to it? Maybe even sing it? There are ways of knowing and then there are ways of feeling. Which is why Compton writes: i use these poems & plant them / inside me i push their rituals through my / pores. If a poet engenders you to feel, then literalism becomes unimportant. We understand on another level, perhaps without consciousness:

my house is a tomb of shadows memories

ghosts the

floor boards smooth from

decades of feet pushing their

fibers into a

pattern of wear the walls torn & rebuilt

Creating a section within the whole, liberated of individuality, enables Compton to swim in his unfettered evocations, literally “blacked out” in a surrealist “borderland” perhaps stemming from “exponential crisis.” Whilst this is clever, it’s also unpolished, warm, approachable, and highly expansive, whereby reader and writer share space and time:

the tree tells me

how it fears extinction i do not ask why i

can see deforestation i understand that

death is becoming faster than growth

house as cemetery ravages its readers in the book’s exploration of complex emotions surrounding death, grief, and the human experience of loss, with the imagery of prevalent death, often depicted in visceral, queer and haunting ways:

i was a cancer that his side of the family

could never cure. i was the blame

for his death. apparently if i were a woman

i would have saved him. my love for him

was fictitious.

how could their son ever love a man? (the enormous room).

Grief is repeatedly portrayed as a multifaceted trauma, encompassing despair, longing, and reflection. Most writers utilize personal anecdotes and observations to illustrate the impact of loss, or examine themes of mortality and the fragility of life, but Compton’s language weaves unsettling truths into bloody narrative, prompting readers to confront their own perceptions of death head-on:

some days, you repeat to me,

you are paranoid;

this room will become your casket. (try)

Compton’s poetry also questions the challenges of personal identity, with lines like: “what heirlooms should i hang from my ears—.” Particularly in the context of sexuality and societal expectations, where Compton holds us close, reflecting on the pain of being misunderstood and the struggle for acceptance in a world that often marginalizes or parody’s queer identity. When he says in love letter to pride “society, / i will never be / what you’ve planned— “He refutes all conventions, even those within sub-groups. Not unusual then, to have recurring themes of feeling like an outsider, with references to societal norms that dictate what is considered “normal.’

heroin in the bathroom stall

while your dick gets sucked by an old fag (jim carroll).

But Compton continually demonstrates in his writing, the internal conflict between self-acceptance and external judgment, illustrating the emotional toll and state of living in non-accepting society. Achieved not just through metaphors conveying the weight of societal expectations on personal identity, but in his very specific style which is immediate and honest to a degree few reach, even in his titles like; “you’ll never want me because your wife’s too clingy or theraw cry of the war of bones” where he burns the reader’s retina with:

i lift my head with pens:

arthritic & weak & cracking.

no one looks twice. i am a flock

of pigeons that shit themselves.

bland & normal. everyone has seen

There is an intersection of love and pain throughout, at times grotesque, sometimes be lyingly simple; this complex relationship between love and suffering, often entwined. Love is depicted as both a source of joy and a catalyst for pain, reflecting the duality of human relationships, but with none of the ‘I told you so’ of a self-conscious writer. The queer-voice isn’t asking for permission, it’s plainly sick of holding back, which I think many of us can profoundly share, in the poem i live where trump is god, where being gay in much of America, even in 2025, is terrifying:

we live looped

in the red belt

of the bible

where gay men

are sin—thread

between two churches:

Compton often deconstructs ideas of queer-love and vulnerability, which in turn disrupt the psyche, speaking to an inevitability of loss, or longing without respite; either way, his reflection is repeatedly stoked through shattering titles like “i wear you like a blood clot,” and the subsequent meat of the poem:

you wait.

i clean out my mouth

with a glass of milk

& swallow

my truth.

Queer love and intimacy is illustrated so honestly, without pastiche or porn, instead with such an aching realism and dirty truism. There are ghosts walking in this manuscript, things you won’t understand but you’ll need nonetheless. Because a universal truth, doesn’t have to be spelt out:

we scour like worms

through the apple

for substance

yet all we

find is the rind,

dried & leathered. (allen ginsberg)

Compton’s choices of mis-en-scene are often linked with the importance of memory and reflection in processing grief and identity. It may be at his core to refute the ‘usual ways’ as a writer, when you read poems like fuck the mfa, you see his refusal to be neatly packaged and sold. That isn’t happening too much in the publishing world these days, as increasingly we’re becoming robotic in our regurgitate and rote repeat control of style and voice. There is rebellion in his rage at this shallow and class-based system:

i want to drown

you in ink. fuck

the hand of the poet

who writes for everyone else.

The book builds toward turning everything on its head, “as the air begins to choke us.” Where memories become a means of connecting with impossible levels of loss and the act of reflection is portrayed as a step in understanding one’s emotions more acutely, although at no point is ‘the answer’ given, because that would imply Compton possesses it, which he absolutely denies.

we walk on the dead;

live on the dead;

we too will be dead. (mourning ritual of a suspension bridge)

Compton asks whether memories can be both source of pain and path to reconciliation, whilst claiming no cure against the pain of living. This most intensely evoked in the lines: “& learn how your end will affect me.” (I mill your hands) again, such simplicity in understanding what cannot ever be reconciled. Compton knows how to speak of loss in so many tongues, it becomes universal:

i waited like a lighthouse

for you to find the surface,

but moments turned into minutes

& your body became another shell

i picked off the bottom with my toes. (you became the holy water)

house as cemetery also considers the influence of societal norms on mental health, how societal expectations can exacerbate feelings of inadequacy and despair, the stigma of mental health, and pressures that cause cycles of self-doubt, with reform that never comes:

where the dying hides.

inside you like a fetus,

ready to claim

the embalming fluid

like warm milk. (the dying kind)

Clearly existentialist, alongside the struggle to find meaning in life and death, these burning surrealist themes are at the forefront, but Compton’s reflections on the ease of learning to die, don’t just exist to reference Allen Ginsberg or Plath or Sexton, but to meaningfully highlight the eroticism and rawness, where the act of writing becomes outlet:

the black mimics night. it immerses me endlessly. i close my eyes & watch it like water filling the corners of my lips. i splinter my nails, carving this letter, describing how i gulped, but could never drink enough to see light again. (the black art)

Compton plays with form repeatedly, delving into the complexities of isolation and emotional distance in relationships. Identifying detachment and creating a voodoo doll of it, where “& in living we knew that death also flourished.” (lady anti-). For any of us in the ‘wrong’ relationship; especially those of us who are queer, there is such a recognition of how impossible it is to put into words without judgement, leaving only the abstraction of poetry to speak those deeper truths; of a husband festering like a tumor illustrating the weight of unaddressed despair on a wider stage:

you were raped

yet too young to cum—they stuck objects

inside you to remind you .” ( were girl

& not boy like them. (transphobia)

Gender is not relevant here; this is a kaleidoscope without code. Identity supplants gender, as the sought-after-ideal, reflecting on the search for selfhood, amidst societal expectation and personal trauma, utilizing surrealism and a phantasmagoric wildness:

i want to bloom but not like you imagine.

i want to redesign dead flowers & make them beautiful again.

i want to make dead things beautiful. (the window is clotted with stains)

Here, Compton examines how memories and trauma shape the speaker’s identity and experiences, alongside the complexity of queer-love, to reveal only the moment, the impulse, and never the unseen ending:

you can’t tell by examining which bones wore what skin suit and by that i mean

the word fag is not engraved in the bones. (after realizing my name means gift from god)

Candice Louisa Daquin, Managing Editor, Lit Fox Books. Consultant Editor, Queer Ink and Raw Earth Ink. Poetry Editor, Writers Resist, Tint Journal. Author, The Cruelty (FlowerSong Press, Fall 2025).

Leave a comment