Deserve: Raymond Brunell

I.

Ms. Keating finds the lunchbox on her desk during fifth period. Empty. The insulated bag sits beside it, unzipped. Aiden Park’s name is written on both in careful Sharpie, his mother’s handwriting.

Third time this week.

She knows who took it. Eli Martinez sits three rows back, eyes fixed on his notebook. His shoulders have that careful stillness of someone pretending nothing is wrong. The classroom smells like dry erase markers and the cafeteria two floors down—today’s lunch seeping through the vents. The other students don’t notice. They’re working on fractions, heads bent over worksheets. But Keating sees the way Eli’s hand moves across the page without writing anything, just tracing patterns while his stomach makes sounds he tries to cover with coughs.

The lunchbox weighs nothing in her hands.

She should walk to the office now. School policy is clear: automatic suspension for theft. The handbook she signed in August has a whole section on it. Three days minimum. No exceptions for the first offense when it’s food, because food theft happens again. It says so right there on page forty-seven.

But she knows things the handbook doesn’t account for.

She’s seen the eviction notice that fell out of Eli’s backpack two weeks ago when he was looking for his math homework. Thirty days to vacate. That was fourteen days ago. She knows Rosa Martinez lost her job at the packaging plant, and knows Eli eats the free lunch like it’s the only meal he’ll get that day. Because it is. She watched him save the apple, wrap it in napkins, tuck it in his backpack for later. For Bella, in all likelihood. His little sister’s in third grade, same free lunch program.

And she knows Aiden needs that food. Not wants—needs. The medical alert bracelet on his wrist isn’t decoration. Type 1 diabetic. His parents pack forty-five grams of carbohydrates exactly, label everything, and include glucose tablets in a side pocket. Last month, Aiden’s blood sugar dropped during PE, and the nurse had to call an ambulance. His parents are careful now. Meticulous.

Eli needed food. Aiden needed food. The empty lunchbox sits between them like an equation she can’t solve.

The period ends. Students pack up, file out. Eli moves slowly, waiting until most of the others are gone. When he passes her desk, he doesn’t look at the lunchbox. He doesn’t look at her and keeps walking.

“Eli,” she says.

He stops. He still doesn’t turn around.

“I need you to stay back for a minute.”

He does. He stands there while the classroom empties, while the hallway outside fills with noise and movement and the ordinary chaos of class change. His backpack hangs off one shoulder, close to empty. No lunch to pack tomorrow. No lunch packed today.

She wants to ask if he’s hungry. Wants to ask if his mom found work yet, if the eviction went through, if he’s okay. But those aren’t teacher questions. Those are questions that make this harder.

“You know I have to report this,” she says instead.

His shoulders tighten. “Yes, ma’am.”

“This is the third time.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

He still won’t look at her. She understands. Eye contact would make him a person asking for mercy instead of a student accepting punishment. She’s seen this before. Kids learn early how to make themselves smaller, how to take up less space, and how to absorb discipline without protest because protest costs more than they have.

“Go to your next class,” she tells him. “I will handle this during the planning period.”

He leaves. She sits at her desk, holding the empty lunchbox, and the word “deserve” rises in her throat like something she needs to swallow or spit out. Who deserves protection? Who deserves food? Who deserves to be hungry?

The word tastes wrong. It feels wrong. But she thinks it anyway because that’s what this moment demands—calculation, measurement, the arithmetic of who suffers less.

The hallway empties. The planning period starts. She should grade papers. She should update her attendance. She should eat the sandwich she brought from home, the one she packed this morning before she knew she would have to choose between two children who both need more than she can give.

Instead, she walks.

The hallway is long. Fluorescent lights hum overhead, that particular frequency that lives behind your eyes. The linoleum squeaks under her shoes. Someone’s classroom door is open, and she can hear a teacher explaining the water cycle. Evaporation, condensation, precipitation. The cycle continues. Nothing is created or destroyed, it is moved from one place to another.

The principal’s office is at the end of the hall. She’s walked this route a hundred times. It’s never felt this long before.

Mr. Alvarez looks up when she enters. “Linda. What can I do for you?”

She sets the lunchbox on his desk. The plastic is still cool from Aiden’s refrigerator this morning. “Eli Martinez. Third theft this week.”

He opens a drawer, pulls out the form. She’s seen it before. The paper is pale yellow, NCR duplicate. The boxes are already printed: Fighting. Theft. Insubordination. Vandalism. Other. He checks Theft without looking up.

“Same student?” he asks.

“Aiden Park. Same lunch, three times.”

“Is Park the diabetic kid?”

“Yes.”

Mr. Alvarez nods, still writing. “Do the parents know?”

“Not yet.”

“They’ll want to know we’re handling it.” He signs the bottom of the form. “Three-day suspension, automatic. I’ll call the Martinez household. Eli needs to leave campus today.”

She watches him fill in the dates. Today through Friday. Three days. Seventy-two hours. The district calculates everything in hours now. Instructional time. Lunch periods. Suspension lengths.

“Linda?” Mr. Alvarez is looking at her now. “Do you need something else?”

She almost says yes. Almost asks what they’re supposed to do when both children are right, when both children need protection, when the only choice is which harm to administer. Almost asks if the handbook has a section for that, a page number she missed, a box to check that says this system is designed to fail them both.

“No,” she says instead. “I’ll let his teachers know.”

She walks back to her classroom. The lunchbox stays on Mr. Alvarez’s desk. Evidence. Exhibit A. Proof of theft that’s also proof of hunger that’s also proof of a system that measures food in gram counts and suspension in days and never accounts for eviction notices or empty refrigerators or the sound a twelve-year-old’s stomach makes in fifth period when everyone’s supposed to be learning fractions.

Her sandwich is still on her desk. She doesn’t eat it.

II.

Mr. Alvarez calls me down during the sixth period. Everyone knows what that means. Maya whispers something to Jordan. Jordan looks at me. I keep my eyes on my desk.

The walk to the office takes forever. My stomach is cramping, but I don’t press my hand against it until I’m in the hallway where nobody can see. I took Aiden’s lunch three times. I knew I’d get caught. You always get caught at some point. I needed those three days of eating.

Mr. Alvarez’s office smells like coffee and old paper. Ms. Keating’s already there. She won’t look at me. That’s how I know it’s bad.

“Sit down, Eli,” Mr. Alvarez says.

I sit. The chair is too big, and I feel small in it.

“You know why you’re here?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Tell me anyway.”

“I took Aiden’s lunch.”

“How many times?”

I could lie. Say once. Say twice. But Ms. Keating already told him. She has to have told him. That’s why she’s here.

“Three times.”

“Three times,” he repeats. He’s writing on a form. I can’t see what it says. “That’s theft, Eli. Do you understand that?”

I nod.

“Use your words.”

“Yes, sir. I understand.”

“School policy is automatic suspension for theft. Three days. You’ll go home today. You can’t come back until Monday.”

Three days. No school. No breakfast. No lunch. Stuck at home with nothing in the refrigerator except the jar of pickles and the milk Mom waters down to make it last.

“Do you understand what I’m telling you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Your mother will need to pick you up. I’m calling her now.”

“She’s job hunting,” I say. The words come out wrong, too fast. “Can I walk home?”

Mr. Alvarez looks at Ms. Keating. She’s still not looking at me. Her hands are folded in her lap. There’s something wrong with her hands. They’re too still. Nobody’s hands are that still unless they’re forcing them.

“You’re twelve,” Mr. Alvarez says. “You need a parent to sign you out.”

“Thirteen,” I say. “I’m thirteen.”

It doesn’t matter. I know it doesn’t matter. But I say it anyway because at least it’s true.

He makes the phone call. I hear it ring four times before Mom picks up. I can’t hear what she says, but I can hear Mr. Alvarez’s side. “Mrs. Martinez. This is Mr. Alvarez at Jefferson Middle School. I need you to come pick up Eli. There’s been an incident.”

Incident. Like I broke something. Like I hurt someone. Like taking food is the same as fighting or vandalism or any of the other boxes on whatever form he’s filling out.

I wait in the office while he talks to her. Ms. Keating leaves. She still doesn’t look at me. The door closes behind her and I’m alone with Mr. Alvarez, the secretary, and the clock on the wall that says 2:47 and the knowledge that I lost three days of food.

Mom shows up twenty minutes later. She’s wearing the nice shirt she saves for interviews. Her hair is pulled back. She looks tired. She always looks tired now.

“What happened?” she asks Mr. Alvarez.

“Eli has been suspended for three days. Theft. He can return on Monday.”

She looks at me. I can’t read her face. Is she angry? Disappointed? Scared? All of them?

“Theft of what?” she asks.

“Another student’s lunch. Three times this week.”

She doesn’t ask why. She already knows. Mr. Alvarez explains the policy. Automatic suspension. No exceptions. Three days minimum. She signs the form. Her signature is neat and careful. She learned English when she was twenty-two, and her handwriting is better than mine.

We walk to the car. She doesn’t say anything until we’re inside. Then:

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Tell you what?”

“That you were hungry.”

I don’t have an answer. What was I supposed to say? We don’t have food and I know you’re trying, and I’m sorry I’m another mouth you have to feed, and I thought if I could make it to summer when school’s out and there’s no lunch to not have, then it would be easier?

“I’m sorry,” I say instead.

She starts the car. “Don’t apologize for being hungry.”

But I am sorry. Sorry for stealing. Sorry for getting caught. Sorry for the three days we’re about to lose.

We drive home. Mom doesn’t ask any more questions. When we get inside, Bella’s watching TV. She’s been home sick with a cold. She looks up when we walk in.

“Why are you home?” she asks me.

“Got sick too,” I tell her.

Mom doesn’t correct me and goes to the kitchen. I hear her open the refrigerator, hear her close it, and I hear the cabinet open. I hear it close as well. She comes back with two glasses of water.

“Dinner at six,” she says. “We have oatmeal for tomorrow.”

Oatmeal. That means the cereal’s gone. That means we’re down to the bottom of things. The last of things.

I drink the water. It doesn’t help.

Day one. Tuesday afternoon into Wednesday morning. I’m supposed to be at school. Instead, I’m on the couch trying not to think about lunch period, about the line in the cafeteria, about the smell of whatever they’re serving today. Pizza, probably. Tuesday is usually pizza.

Bella asks again why I’m home. I tell her I got in trouble. She asks what I did. I tell her I took something that wasn’t mine. She asks what I took. I don’t answer.

Mom made oatmeal for breakfast. One packet split three ways. She added extra water to make it seem like more. Bella ate hers. I ate half of mine, said I wasn’t hungry, and pushed the rest to Mom. She pushed it back. We went back and forth until she said, “Eli. Eat your food.”

So I ate.

My stomach is cramping now. It does that—cramps when I eat, cramps when I don’t. There’s no winning.

Wednesday afternoon, Mom comes home from another interview. I can tell from her face that it didn’t go well. She doesn’t say anything and hangs up the nice shirt, changes into her old clothes, and opens the cabinet.

One can of soup.

She measures it like she’s doing chemistry. One ladle for me. Half a ladle for Bella. Half for herself. She adds water from the tap, and heats it on the stove. Calls it broth. Her hands don’t shake when she pours. They’re steady. Certain. She’s done this math before.

We eat at the table even though there’s not much to eat. Mom insists. She says eating together matters. She says it’s important that we stay a family even when things are hard.

Bella talks about school. About her friend Maria. About the book they’re reading in class. Mom nods, asks questions, and acts like everything’s normal. Like we’re having dinner, not dividing one can of soup three ways. Like this is enough.

It’s not enough. But we pretend.

After dinner, I lie on the couch and try not to think about Aiden Park’s lunch. The sandwich with the crusts cut off. The apple slices in the small container. The cheese stick. The cookies his mom always packs. The forty-five grams of carbohydrates measured exactly.

I think about it anyway. The sandwich bread, soft white, crusts trimmed. The apple slices that stayed crisp in their container. The way the whole lunch smelled like someone’s kitchen, like home.

Day two. Thursday.

My stomach stopped growling. Now it hurts. A tight cramping pain that sits below my ribs and doesn’t go away. When I stand up too fast, the room tilts. I drink water from the tap. It helps for ten minutes at most.

Bella went back to school today. Before she left, she asked if there was anything for lunch. Mom said yes. She packed her a sandwich—two pieces of bread with nothing in between. She folded it with care, put it in a plastic bag like it was a normal lunch. Bella didn’t ask what kind of sandwich. She already knew.

After Bella leaves, Mom sits at the table with the newspaper, circling ads. Her pen moves across the page. Circle, circle, circle. So many circles. She’ll call them later. Leave messages. Wait for callbacks that may come or not.

I should help. I should do something. But I’m tired in a way that sleep doesn’t fix. Heavy tired. My arms feel like they’re full of sand. My head hurts. My stomach hurts. Everything hurts.

“Eli,” Mom says. She’s not looking at the paper anymore. “Come here.”

I sit down across from her.

“I found something,” she says. “Night shift at the distribution center. Four nights a week. It’s not much, but it’s something.”

“That’s good,” I say.

“I’ll start on Monday.”

Monday. The day I go back to school. The day this suspension ends.

“They want someone who can start right away,” she continues. “Someone who doesn’t need training. I told them I could do it.”

She can. Mom can do anything. She worked at the packaging plant for six years before they laid off half the line. Before that, she cleaned houses. Before that, she worked at a hotel. She’s always working. Always trying.

“We’re going to be okay,” she says. But she says it like she’s trying to convince herself.

I nod. “We’re going to be okay.”

I don’t know if either of us believes it.

That night we eat rice. Just rice. Mom makes a whole pot with the last of what’s in the cabinet. The steam rises when she lifts the lid, smells like nothing and everything at the same time. She says we need to have enough for tomorrow. We eat it plain. No butter. No salt. Nothing. It’s dry and hard to swallow but we eat it anyway because tomorrow there might not be anything.

Bella cries a little. She says her stomach hurts. Mom holds her, tells her it’ll be better soon. Tells her we have to make it through the week. Tells her that Monday everything changes.

Monday, Mom starts her new job. Monday, I go back to school. Monday, the cafeteria serves lunch again.

Two more days.

Day three. Friday.

Bella stayed home. She said she felt sick. She’s not sick. She’s hungry. But Mom let her stay anyway. Maybe because it’s easier to divide nothing between three than to pack nothing in a lunch bag.

We don’t have rice anymore. We don’t have oatmeal. We don’t have soup. The cabinet’s empty except for the pickles and a can of green beans from two years ago that might still be good or might not.

Mom opens the can. Green beans for breakfast. We eat them cold, straight from the can. They taste like metal and salt and the back of the refrigerator. Bella makes a face but eats them anyway. I eat mine. Mom eats hers.

After breakfast, Mom says she needs to go out. She needs to see someone about something. She doesn’t say what. We know what. She’s going to ask Mrs. Clarke next door if we can borrow something. Some rice. Some bread. Anything.

She comes back an hour later with half a loaf of bread and a jar of peanut butter. Mrs. Clarke’s peanut butter. The kind with the oil on top that you have to stir.

“Lunch,” Mom says.

We make sandwiches. Peanut butter on bread, no jelly. It’s good. It’s so good I want to cry. Bella eats two. I eat two. Mom eats one and says she’s full. She’s lying, but we don’t argue.

That afternoon, Mom takes a nap. She never naps. But today, she lies down on her bed and closes the door, and I hear her crying through the wall. Quiet crying. The kind you do when you don’t want anyone to hear, but the walls are thin and the house is small and there’s nowhere to hide. The sound is worse than hunger.

Bella and I watch TV. Some cartoon about talking animals. We don’t talk. We sit there, hungry, waiting for Monday.

My stomach doesn’t hurt anymore. It’s gone quiet. Empty. I press my palm against it anyway. I feel the space where food should be. Where food used to be three days ago when I took Aiden’s lunch and thought I was solving something.

Mr. Alvarez called it theft. I thought it was eating.

Tomorrow’s Saturday. Two more days until Monday. Two more days until school. Until breakfast in the cafeteria at seven-thirty. Until lunch at noon. Until I walk past Aiden Park’s desk and see his lunchbox—full, labeled, measured exactly—and know that Ms. Keating chose him.

She chose right. He needs that food. His bracelet says so. His parents’ careful handwriting says so. The forty-five grams of carbohydrates say so.

But I needed it too.

I don’t know what that makes me. A thief, it seems. That’s what the form said. That’s what the three days mean. That’s what I am now.

I press my palm harder against my stomach. Feel the emptiness. Feel the quiet. Feel Monday coming, close enough to count.

Raymond Brunell writes literary fiction exploring institutional systems, class, and survival. His work has appeared in Across the Margin, Swim Press, Writers Hour Magazine, Little Old Lady, FLARE Magazine, and over thirty other venues. He lives in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. More at www.unbound-atlas.com.

Where the Mind is Without Fear. Where? by Sukhjit Singh

Vani runs around the grass patch chasing something only fifteen-month-olds can see. Her screams of joy are pure and unfiltered. But my mind is at a different place and in a different time – those few days in Delhi’s life forty years ago when screams of girls were anything but joy.

I finished reading ‘The Untold, Unheard Stories of Sikh Women,’ a book on 84 anti-Sikh riots this morning. I thought I had read everything that was written on those three days of carnage. Clearly, I was wrong.

***

The mob is outside my door. I have secured all three bolts and locked the double secure lock, but this door will not last a sustained hammering. There is no time to waste. I get the plyboard from the storeroom and place it against the door. The plyboard is thick and the exact size of the door. It takes some effort to drag the heavy teakwood dining table to the door and then to make it vertical. Next, I pull the sofa centre-table and jam it against the dining table. All the dining table chairs go on top in a pile. I still hear the mob banging the door and cursing me and my community and baying for our blood.

Suddenly, there is silence followed by some voices – most likely the other residents of the floor. I am sure the Ahmads will not step out but the other two families – Srivastavs and Kumars might try. But two elderly couples that they are, they will not win this argument with the mob and will retreat shortly. Maybe they will get phone calls from their children sitting abroad enquiring about their safety and that will be the end of their physical intervention. Probably, they will try to get some help via their phones but even they know it’s not coming today. Not for us – the declared ‘traitor community’ for the day. They have seen this happen multiple times over their lives. Mr Srivastav retired from the police force in 2021 after serving for over 40 years in the capital city and knows this better than anyone, from 1984 anti-Sikh pogrom to 2020 North East Delhi riots he has witnessed system’s complicity in all shades of blood. Still their pleading with the mob buys me time.

The gas stoves are on and karahis full of oil. I get the bag from the upper cabinet in storeroom. All the gear is in there. I lay the wires from the AC power sockets to the metal grills in the balconies. I keep the facemask, the heat-resistant gloves, and the hammer at the centre of the hall.

My wife is in the bedroom, trying to get Vani to sleep. She reluctantly agreed to give three spoons of the medicine to Vani. I bought this medicine for her first flight. She was six months old, and the doctor recommended we give half a spoon if the baby doesn’t stop crying in the plane. We never used it. Three spoons at her age now should put her to sleep in under ten minutes.

All the curtains are drawn.

I am ready.

***

“You bought these big flowerpots to plant pudina?”

“No. I will get the plants soon. In the meantime, what’s the harm in enjoying chatni from some home grown pudina!”

“Just like we were able to enjoy saag from home grown palak last year! Your kitchen garden experiments are not going to work in Gurgaon apartments.”

“Hum honge kaamyaab ek din.”

***

‘There are 15 of them.’ Aakash keeps me updated over chat. ‘They are carrying trishuls, swords, knives, sticks. Don’t see a gun or a pistol.’

There were over a hundred of them when they reached the gates of my society. The guards had locked the gates from inside. But what’s a five feet gate to a mob fuelled by hatred and propelled by support and protection from the state. A few of them jump over the gates and that is all it took for the two elderly security guards to hand over the keys.

This is a relatively affluent society. But that’s no guarantee of safety. Those who run the mobs know who lives where. There are only a few of us ‘traitors’ in this society – only three households, so 15 goons from the mob stay once the gates are opened. Rest move their rage to the gates of the next society.

By the time I hear a crack in the door I have had time to prepare.

Two flowerpots are empty of their mud. The mud forms a small bund around the furniture that is pushed against the door.

I get a bucket of hot water and pour it under the furniture next to the door. The water runs towards the door and underneath it. Next, I place the wire on the wet side, step back and flick the switch on.

‘Sala paani daal raha hai idhar.’

‘Haram khor hum kya slip kar jayenge.’

‘Pani se bhagayega humko. Todo sala Darwaja. Jaldi.’

There are four or five of them outside. Aakash tells me that rest of them are in the next tower – where the other two traitor families live. Wet floor and live electricity wire needs an idiot to complete the circuit – touch the wall or the grill of the stairs or place their metal rods and trishuls on the floor. First one and then another cry confirms that most mobs consist of idiots. As they try to help each other I pour another bucket of water. The banging on my door stops. But not the chaos outside.

***

It’s been two years since Vani’s first step. Standing by the children’s play area, watching our girls play every day for an hour or so, slowly but steadily Aakash and I have developed some camaraderie. Our discussions started around our children’s games and over past two years we have covered topics from spiritual to philosophical to political.

He is a kindred spirit.

But more importantly he lives two floors directly above my flat.

***

The rope ladder hangs through the bathroom window of Aakash’s flat on the far side of the building into the shaft area. Thanks to all the pigeons and monkeys in the area the shafts are covered. I ask Aakash to pull the rope ladder and send the heavy-duty electricity wire up. I ask him to plug it in the geyser socket.

Once the rope ladder is back, I kiss my daughter and tie the baby-carrier around my wife. I hug her.

“For our baby,” I tell her.

“You must come too.”

“You know I can’t. If there is no one here for them – they will go looking for us in other flats.”

We hug for the longest time.

“Now go.”

***

One evening as our daughters are chasing each other in the park and Aakash and I are wading through our day’s topics, I bring up the news of the fire in an apartment building in the city and how the flats on which the fire was had no escape route.

It doesn’t take much convincing as the safety of his family is involved.

A few days later I keep a 20meters long rope ladder in his storeroom.

***

My intercom rings.

It’s Mrs Srivastav.

“Beta, they have left our floor, but I see them getting the bamboo stair from the garden. They are trying to enter through your balcony. I am worried beta. Maybe you should leave from the front door now.”

“And go where madam? Don’t worry, I will handle them in the balconies.”

“Mr Srivastav has called the police so many times. No one is coming this way. I don’t know how we can help beta.”

“You can.”

“How?”

“Switch on your geysers. Start filling buckets with as much hot water as possible. Get these buckets in the balcony on my side of the building. And call everyone else in the building. Whoever wants to help. But tell everyone to wait till I give a go ahead.”

“Ok beta. I will get this done.”

***

“Why did you order a twenty-litre tin can of refined oil and 2kg red chilli powder?” My wife asks as I move the items from the door to the storeroom. It’s a fair question – we use minimal chilli in our food and use ghee for cooking. I don’t answer her. I can’t answer her.

A short while later I hand her the book. The book that I read six months back and which has been on my mind ever since.

***

They have tied two bamboo stairs together, but this doesn’t reach the second floor. Then someone in the group sees the gas pipeline running all the way to top of the building. There is a discussion and one of them starts climbing the pipeline. The pipeline leads to the kitchen balcony of every flat.

The person is moving up gradually. I step in the balcony and say as loudly as I can.

“Please stop.”

The group starts laughing.

“Aa rahe hain hum madarchod haramke.”

“Please stop.” I say a second time.

“Chad Munna chad. Kaatna hai haramkhor ko.”

“I am saying for the third and last time. If you care for your life Munna please stop and get down and go away.”

Munna just doesn’t care. He is mad in his rush up the wall. The rest of the group are encouraging him and waving their swords and trishuls.

I step inside the kitchen, fill a tea pan with boiling oil from the karahi on the gas stove. I step back into the balcony.

“Please stop and go back.”

Munna is almost near my balcony. He only grins at my request. I know this is his last grin.

As the hot oil hits his face he cries out and his hands let go of the pipe. A second later he meets the ground with a thud. The group goes silent.

***

Sometimes this is where I stop thinking about how it will play out. But the thoughts keep coming back uninvited.

The mobs don’t give up this easy—the thoughts reason with me.

I look at Vani walking alongside, holding my finger, her squeaky shoes squeaking just like her, in joy.

And I won’t give up that easily as well—I reason back.

***

An hour of silence in the society.

Mrs Srivastav confirms that all households have hot water buckets in their balconies and ask if these are still needed.

I assure her that there is need. Just keep the geysers on. And be ready.

Aakash calls. He sounds troubled.

“There are two trucks full of them now in the society.”

“Let them come.”

My flat’s light goes off. So, they have found the power switch for the floor. Soon I hear banging on my door again.

In the one hour break I have piled on more furniture in the gallery in front of the door. All the stools, two small cupboards, shoe racks, the foldable stair. Then I took the 2kg chilli powder and threw it all on the furniture.

I hear my door crack and break. There is a loud cheer. The hammering stops and lots of bodies push against the door. But nothing moves. They curse and spit and start hammering again.

The wire coming from Aakash’s home has multi-socket extension board at the other end. I connect the wires going to balconies to it and connect a table fan to it. I put the fan on max speed and point towards the furniture in front of the door.

I wait for them to make an opening in the plyboard with their hammering.

The plyboard cracks. A few more blows and it has big holes in it.

I put on a face mask and switch on the fan.

A single cough. Multiple coughs.

Curses.

Men running down the stairs.

Once again, the area outside the door is empty.

***

“The book you gave me to read is gut wrenching.”

She is trying to teach Vani the Punjabi alphabet but can’t focus. Vani breaks free and runs and grabs my legs.

“Something like that can happen again,” she says as if to herself.

“Don’t worry honey. This is not 84 anymore.”

“With so much hate around, it is worse than 84. Who knows when and on whom this hate finds an outlet.”

In my heart of hearts, I know what she is saying is true.

“What if something happens and the mobs come looking for revenge from our community again?”

There are no words with which I can answer her question.

Vani rushes away and is trying to get Alexa’s attention to play her the party freeze song.

“Don’t worry honey,” I tell my wife.

‘I am getting ready for them.’

***

This is the final act.

They all have gathered around the tower. There are a lot of long bamboo stairs now.

Four stairs reach my balconies. Two each on both sides of the flat.

Four men wearing helmets climb the stairs with fibre shields held over their head.

The shields and helmets are police provided.

I have Mrs Srivastav on call.

“Madam this is it. You sure folks will be able to do this.”

“Yes beta. We all might be old and retired but we have some honour.”

“Ok madam. Go ahead once you get my message.”

I step into one of the balconies. On the side where I think the leader of the pack is.

“Neta ji,” I speak as loudly as I can. “This is my last warning that all of you leave immediately.”

Neta ji isn’t much a leader. His words of abuse are the same as rest of the gang.

As the first shield covered person reaches my balcony and puts his hand on the metal grill, he cries and falls back. This is enough to stop the other person in his upward march. Soon a cry is heard from the other side of the flat followed by a fall and a thud.

“‘Neta ji, leave now.”

Neta ji looks at me with all the anger he can muster.

“Hum mar jayenge par tujhe kaat ke jayenge.”

“So be it,” I whisper.

And I send a text to Mrs Srivastav. “Now.”

Nearly thirty residents step into their balconies and empty buckets of hot water one after the other.

I can’t help a smile when I see the colour of the water. It is almost kesari. That’s a lot of haldi to heal the burns. Mrs Srivastav isn’t without style.

The goons run.

The elderly security guards close the gate behind them.

I heave a sigh of relief.

I drink a glass of water.

And then I start removing the furniture pile from my door.

I am not sure if I can get this world back in shape, but I will get this home, her home, back in shape before my daughter wakes up from her sleep.

***

For days, weeks, months, after I had read the book, this is all I can think about.

Sometimes I tell myself that things will not turn this bad, will not go this far.

Only sometimes.

One day I might wake up into that heaven where the mind is free. Where my land is just. But for now, my mind plans and my hands prepare.

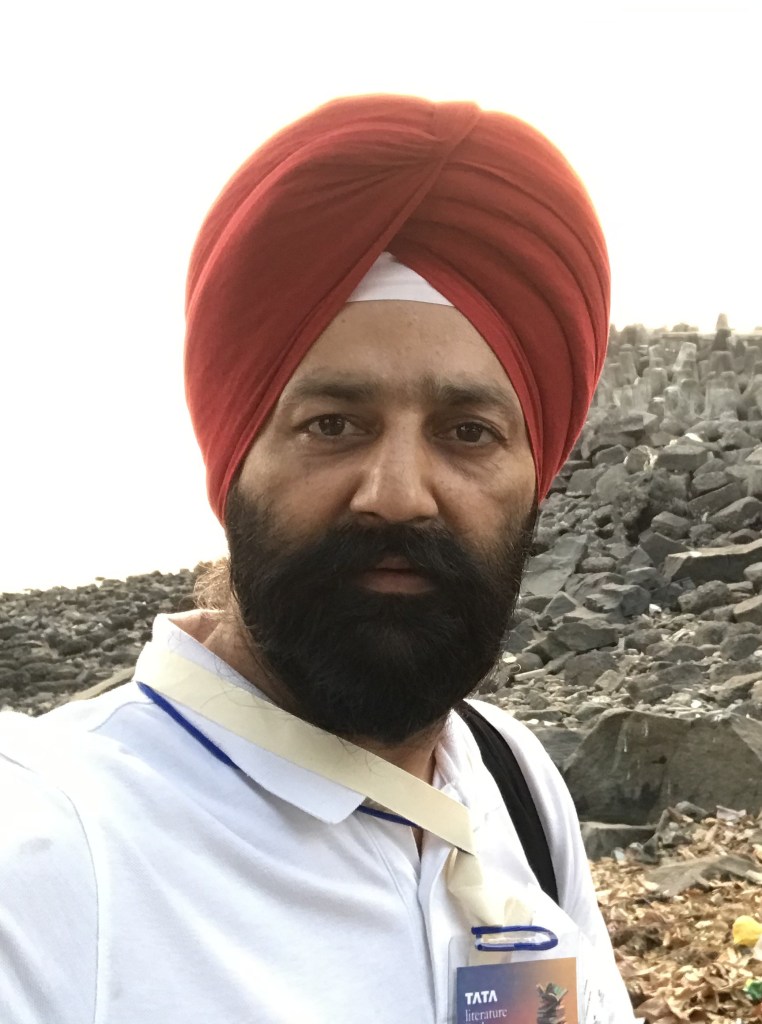

Sukhjit Singh is an IIT Delhi alumnus. His writing started with a travel blog in 2005. A memoir of his school days was published in 2011. The focus of his current writing is contemporary socio-political themes. His short story Mandi, on agrarian distress, won the jury award at the TATA Lit Live MyStory Contest 2023. His writing has appeared online with Parcham, The Tribune and Kitaab. He is a South Asia Speaks 2025 fellow. He is currently working on his first novel.

The Apotheosis of Himmat Dewan by Armaan

The laughter ceased, the boys stiffened, and the chalk hit Himmat square between the eyes.

Dewan, enough of that nonsense!

But sir—

Quiet!

All the boys in biology class were agitated. Shifting and squirming in their seats, which were really just long thin benches and each cut from one log. All but he, Himmat Dewan. He had been perfectly still.

Abhimanyu Rathore and Devsharan Das sat on either side of Himmat, and had been bombarding his exposed flanks with whispered questions.

Himmat, what are you going to do?

What’s it for, Himmat?

Chal na, Himmat. Why you?

Tell, no.

From the rear, Prabhu Pratap had been tapping the back of Himmat’s head with his blunt 2B pencil in a discernible rhythm, peppering the silence between each beat with salvos of—Bataa na, Himmat.

Mr. Rai, having heard only one name from behind his back, had cocked his arm and aimed accordingly.

The chalk left a little white bindi on Himmat’s head, and stifled laughter rippled from the front row to the back.

As I was saying, the mRNA—

Abhimanyu and Devsharan had snickered when the chalk hit him—forehead white and cheeks deep red—and then assumed a solemn expression, as if suddenly overwhelmed by the emotional weight of DNA transcription, of the mighty nucleotide, and of the elegant double helix, which, when tweaked by a few amino acids, turned boys like them into chimps.

The chimpanzee could well have been the superior species when up against the boys in his class. Always the most well-dressed in his class, the most diligent in notetaking, and the most rigid in his walking—often likened by his dorm mates to an erect penis—Himmat alone felt like a civilised being. Not out of an inherent respect for the values of a boarding school founded by wrinkled white men, but out of an extreme sense of self-preservation. The Masters lauded him and he never got into trouble, except when it involved the violent whims of his peers. Nerves frayed, but polished on the outside. Like the shoes he spent rubbing every night until he could see his own face in them. Order kept him alive. He knew how to tie all three types of ties. He had an instinct for knowing when a prefect had entered the adjacent room, and stiffened immediately. He had perfected the art of standing absolutely still at assembly, so that he could hear the blood flowing in his ears, and the boys around him falling like flies, picked out by prefects and sent outside to be slapped around for making noise, for unpolished shoes, for looking at a twelfth-year the wrong way—

But that morning’s assembly, what a nightmare. All the eyes penetrating through him, all the way. This lone boy, in the tenth year, damned beyond doubt by a jury of his peers. The assembly hall spinning. The air heavy with the smell of sportsman’s sweat. All the tenth-years shifting their weight from one leg to another like uncomfortable penguins sensing a seal among them. Himmat’s own skin electrified.

It had been short. They had shuffled into their standing places in the hall without much yelling on the prefects’ parts. The boys of Gurcharan House stood together. Among them, Himmat. He had the beginnings of a moustache above his upper lip. Tall for his age, athletic, and quieter than the rest. In the silence that always governed the hall before a prayer was said, there was a cough. And then another. They found ways in assembly to communicate with hand signs and facial expressions without attracting the prefects’ attention, mimicking the Headmaster’s voice as he announced the most immaterial things in the world—eleventh-years and twelfth-years to attend the career fair next Monday, eighth-years to sign up for their field trip to the museum next week, eleventh-years of all Houses to meet their respective Housemasters outside the auditorium after assembly. Communication elaborate enough for a linguist to think what a pity it was that nobody had sawed open the skulls of these boys to hypothesise on language systems among apes.

The Headmaster, barely visible on the stage so far away, had never really tended to mince his words, but that past week, on account of a string of cannabis-related incidents in Balram House, he had minced them into pulp. Protracted and periphrastic comments on the importance of discipline and community and the School’s reputation for churning out greatness and then his usual affair at assembly of inspiring the next generation of leaders and the model man and the beauty of the campus. And every morning for the past week the boys of tenth-year had been waiting to hear about their scheduled sports meet with Fairfield Girls’ School, and they heard nothing.

All those wishing to participate in this year’s cross-country run should report to Sardar Khan after assembly.

Himmat had heard Devsharan Das and Prabhu Pratap, both in the row behind him, groan. He did not move, even though one of them kept kicking at his heels.

Ahmed Abbas, Tejvir Singh, and Kamal Patel, please report to the Headmaster’s Office at break time.

The usual suspects. Twelfth-years, all of them. A murmur rippled through the crowd, brutally shushed in no time. Three boys called to the Headmaster’s office—at break time? Surely, an escape party—scaled the walls and off to Fairfield Girls’ for the night, or the cinema, or the theka. Or perhaps in connection with the cannabis found in Balram. The tenth-years would never know. Himmat would never know. There was little that the twelfth-years let slip about what they did in darkness. No one in tenth-year had ever been called up to the Headmaster’s yet, so the secrets of its doors were not known to them. And the Headmaster always said ‘break time’ the way news anchors said ‘war time’. Carried the same gravity, the same audible gasp meant to be drawn from an audience’s lips. At least it always sounded so to Himmat. Like that quote they had put up on the blackboard in history class—“in war time, truth is so precious, she should always be attended by a… something of lies.”

A few more announcements. The assembly was really beginning to feel long, with the shirts sticking to their backs and the—

Himmat Dewan, please report to the Headmaster’s Office at break time.

He himself had not even heard it. Far away he had heard ‘report to the Headmaster’s office’. Sounded alien to him. Only when the boys of Gurcharan turned to him all at once with the synchrony of machines, all their confusion turned to wonder, did he realise a fading echo of his name was in his ears, spoken in the Headmaster’s voice. It had been unbelievable. Report alone? Surely not alone. What had he done? Surely nothing.

Mr. Rai checked the clock lodged between diagrams of reproductive systems on his classroom’s right wall—just flicked his head ever so slightly, barely even noticeable, because he knew that if the boys saw him do it, they would slam their notebooks shut and make for their bags —as he dragged the chalk across the board. Three minutes to the bell. Here was anarchy. Here was the end of days. The failure of reason, if there had ever been any, and the unremembering of human knowledge until the end-of-term exams. Abhimanyu and Devsharan and the rest knew when to rise from their seats, right before the bell even rang—such was their faith in it, and such was its guarantee of deliverance.

Not Himmat; he always waited for the bell to begin packing his things.

He had learnt in English class last year that spring symbolises hope in the poetry of Emily Dickinson, yet April on campus felt like anything but. It was hot very suddenly. Himmat hated the heat. He could not imagine that anybody liked it. Some boys always fainted from the shock of a passed winter. The month felt dead, like the last cool breeze had just brushed past them. Like, he imagined, as he thought they all did, silently each one as they fidgeted with their pens, a ship on a sea with no wind—mile upon translucent mile of glass, and a wooden box brimming with men waiting for death.

Expectedly, yet somehow still sudden, the bell—heralding break time. And then there were two— Himmat and the horde—one bound for the Headmaster’s Office and the other to the dining hall, where chai pakoda waited.

Himmat picked up the pace as all of 10B biology pushed past him through the decades-old oak door. It creaked when Mr. Rai shut it behind Himmat for a few minutes of peace. For a moment, in the wave of white shirts, red ties, and brown pants that crashed over him, Himmat felt as he had on his first day—lugging his grandfather’s freshly repainted air force trunk, holding on to his beltless trousers, and conscious of his oversized Oxfords clopping on the stone walkways. All those strange faces, sprouting hair and acne. Belligerent and bracing for a life confined to campus walls. In three years, their penchant for aggression had only grown.

The stone that snaked between the school buildings was lined with red brick, the same bricks the buildings were made of. In dusklight, it all turned red, every little corner of campus. Nothing escaped it, that tinge of fire. Himmat remembered how it had felt to walk around campus cowering on his first day, in another distant April. His mother’s eyes red and his father’s chest swelled with pride. It had all looked exactly as it did now, waking from winter, smelling of trimmed branches and cut grass. Then too he had noticed the bricks laid in authoritarian fashion. They made campus look like a whole other country, very unlike the tin roofs and adulterated concrete outside its walls and the asphalt cracking under truck tyres and the little momo stands that were washed away with unsuspecting stray dogs every monsoon.

The crowd melted away to the dining hall and he found himself walking alone. In time, he reached the Headmaster’s office. He waited a few moments and then saw Ahmed Abbas, Tejvir Singh, and Kamal Patel leave the office through its doors of polished wood. The doors were tall, reaching all the way to the ceiling, and following them up with his eyes made Himmat dizzy. The three twelfth-years stumbled out, snickering. He did not know them personally; they had once cornered his dorm mate running an errand in Balram and slapped him around in the boarding house corridor. That was all he had heard about them. They glanced at Himmat, talking among themselves. He was still. He remembered that story about how bears and wolves do not attack men who play dead. He looked straight ahead, holding his breath, and Kamal Patel shouldered him roughly as he walked past. The other two burst out laughing.

The Headmaster was a large white man with a small face, whose skin was beginning to melt off. The more it did, the more severe grew his frown. He sat at a mahogany desk with the discomfort of one who has never truly stood up. He always greeted every boy that entered his office with an ‘Ah’ before saying his name like he knew him personally. The Headmaster always maintained a certain distance from the boys, who went silent when he entered a room and never spoke to him unless spoken to. Good headmasters are like good generals. They know what happens in the barracks, but they never know too much. To the students, as to soldiers, their leader was always a hollowed out figure, his insides spooned out for the sake of doctrine. They could not comprehend that he has his own thoughts. Worse still, his own thoughts about them. Which was why Himmat was so startled when the Headmaster greeted him like an undercover detective greets a mobster after years of tracking him—as if he alone knew Himmat so intimately, so dangerously well.

Ah, Himmat. Come, come.

Himmat remained standing, straight as an arrow. The Headmaster did not ask him to sit.

Do you know why you are here?

No sir.

You have missed fourteen classes this semester.

Sir?

Fourteen classes. You have missed fourteen classes.

No sir.

It says so right here. Are you lying? The ring on his left hand produced a brief but jarring sound when it hit the mahogany table as he took his hands off the ledger before him, leaned forward, and interlocked his fingers.

No sir. He jumbled his syllables so that it came out like ‘nossur’.

Give it up, young man. There’s no dignity in dishonesty. Now—

He pulled out a stack of yellow-coloured cards from a desk drawer.

—the question of what to do about it.

Himmat’s eyes were fixed on the cards. The Headmaster hastily wrote on one and handed it to Himmat—held gracefully between his middle and ring fingers—almost unconsciously, like he was already thinking about the next task while his hands moved themselves.

GATED CARD

This card is to show that ___HIMMAT DEWAN___

is hereby gated for a period of __FOUR__ weeks.

He may not leave the campus for outings, competitions,

and any official work except in the case of emergencies,

and is barred from visiting the tuck shop.

The headmaster’s signature, sharp and in dark ink, oppressed the bottom right corner.

That will be all, Himmat. A copy of the card will be sent to your Housemaster. Do not be late for your next class. And please, no more bunking.

Sir?

Yes?

What dates does it say I’ve missed class?

The Headmaster’s frown grew deeper. Unused to such requests, he nevertheless ran a finger down the page in front of him. The third and fourth of this month, he said. All classes on either day. Fourteen in all.

Himmat blinked. He remembered the third and the fourth. Or rather, he remembered the night of the second, when he had passed out on the floor of his dorm and the prefects had to haul him into the school clinic, where he lay incapacitated by fever for two days. Perhaps the nurse had forgotten to log his admittance. He remembered shuffling into class again on the fifth, and even telling his Masters that he had been sick. He thought it worth mentioning to the Headmaster. He knew it was worth mentioning. But the words remained rumblings in his throat as the large white man said, once again—That will be all, Himmat.

Again the brick looking down and up and sideways at him. From everywhere. Again the white shirts and brown pants pushing past him on their way to class. Himmat’s bag felt heavy. All the red campus choking on dust thrown up by boys racing the bell.

Next class—history. Break time had not yet ended, but it was time to start making his way to class. He sat down heavily in his seat, his bag slowly falling off his legs and onto the ground. Around him they gathered—Prabhu Pratap, Vinayak Rao, Bilal Sharif, Abhimanyu Rathore. They asked to see the card.

Here. They passed it between themselves.

Oh, wow.

What? Himmat snapped. Now that he knew there was no real crime, that it was a technicality over which he had been gated, his anger had started to bubble up and out of his mouth. And even the size of all the boys before him, all these sweating, halfhaired chimps with arms like cricket bats, did not deter him from expressing it.

Don’t you realise?

Arrey, what?

You’re the first person from our year to be gated.

Himmat gulped. He was right. The day was getting worse by the minute.

Oye, all of you—Himmat’s gated, look at this.

He squirmed.

This is so cool.

What? Himmat’s neck snapped in the direction of Prabhu Pratap.

This is so sick—what did you get it for?

Ya bro, tell us, na.

Bhai, you’re always so quiet, ab toh you can talk.

No, no, I don’t—

Arrey, just tell.

Silence. Then—Himmat’s mouth crept into a smile for the first time that day. No. It’s a secret.

He probably beat the shit out of someone and isn’t saying.

No bro, must’ve smoked.

You’re mad. He wouldn’t smoke.

Why? My brother also started smoking in tenth.

But he’s such a stickler for rules.

Bhai pakka, he must have a phone.

No fucking way. Do you, Himmat?

Himmat’s eyes darted back and forth as the boys of 10B history went on. They all crowded around him, shoving and scratching to see the card. It was in his hands, getting crumpled under the scuffle. Their eyes were at the edges of their eyeholes as they strained to read it. Some of them looked at the card, looked at Himmat, and looked at the card again. Their disbelief gave way to wonder—wonder at this boy who moments ago had barely been a human being to them, but who had now taken the first step among them into manhood.

Their heartbeats were synchronised; he could feel all the chests thumping against his arms and back and he sensed hair and hot breath all around him. It was only for a moment, but the heat of their bodies seeped underneath Himmat’s skin. He had always hated the heat, but now, it felt purifying, drawing out from him all that he kept hidden in a body confined to itself and closed off to the world. For the first time since that distant April, when he had first noticed the bricks of campus, Himmat felt his shoulders drop. His breathing slowed and his face unclenched itself. His fingers had newfound sensation in them. Like he could use them to throw something, to punch someone, to stick them in someone’s nose or ears or eyes, or like he could use them to crumple up paper balls and aim them at teachers’ heads. All the others went silent when faced with his silence—they stared at him and he stared back.

Then the bell rang, the talking ceased, Mr. Das entered the room, and the boys dispersed to their seats.

Armaan is a London-based writer whose work has appeared in Condé Nast Traveller, The Quint, and HIMAL Southasian. He enjoys bouldering, dancing in his room, and pointless arguments, and he intends to write frantically for the rest of his life.

Featured Artist: Shiwangi Singh

Shiwangi Singh is a student of History, she completed her Graduation and Post-graduation from Presidency University, Kolkata. She is an independent researcher, and a freelance self-taught artist as well and is connected with numerous Little Magazine publications and has worked on numerous book covers.

Leave a comment