When you sit down with a collection of short stories, what often takes you by surprise is the depth and intensity that writers can explore through this genre. These narratives lay bare the fragility of the human condition; not confined to a few individuals, but spread across experiences and magnified so that readers can recognise their own emotions within them. What emerges is a sensitive portrayal of characters who are neither too weak, nor strong enough to break free, suspended in complex emotional landscapes.

For non-Bengali readers like me, this anthology is a gift. The translators deserve particular thanks for bringing us stories that might otherwise never have reached us. Their careful selection and nuanced renderings convey an array of emotions that only a skilled translator can bridge between writer and reader. This underscores how crucial translations are in opening up the rich oeuvre of literature in other languages to wider audiences.

Mousumi Roy’s Mother Shashti’s Beloved and the Forsaken Ones captures the delicate ties that bind people together; ties that can fray under the weight of material desires. The story’s sensitivity is heightened through the eyes of a child narrator, reminding us of the power of perspective when a story is entrusted to the right voice.

Not sharing these memories would feel like a sin. After all, I was a silent witness to those events. When the worm of corruption devours the human mind, people can sink to unimaginable depths. No other creature can match the monstrosity of humans.

Biswadip De’s Walking Forward explores another form of fragility: the gradual erasure of memory. The story depicts a father losing his sense of self and a son’s desperate wish to bring him back to the remembered past of childhood and growing up. This slow loss is painful and inescapable.

How I wish I could enter my father’s head! There, the mound of memories keeps gradually decaying and crumbling. I have seen videos of riverbanks eroding. Is that how repositories of preserved human memories fall apart? And as they break, some memory of long bygone days might resurface–whoosh! I kept staring at Baba’s face. Looking at him, it’s impossible to determine what’s happening inside. Baba grows more lifeless with each passing day. The doctor has asked us to stir up old memories. I do so. But I don’t see any responsive hint of interest or enthusiasm on Baba’s part. Maybe he doesn’t remember at all! Or perhaps the bits and pieces he remembers are so fragmented, tattered, and torn that no needlework can patch them up.

The stories in this collection repeatedly remind us that the world is neither an easy space to inhabit nor a simple one to navigate. People move between blind faith and deep scepticism; appearances often mask fragile egos and cunning intentions. Few stories revisit the tumultuous decades of the 1970s and 1980s, when ordinary lives were caught in the crossfire of wars and political unrest. Yet amidst the violence, traces of kindness and yearning for connection remain. Debabrata Mukhopadhyay’s Worth of Time for the Worthless examines extreme isolation, whether among others or within oneself. It brought to mind Japan’s rental family services for lonely individuals, but this story goes further, delving into the texture of solitude itself.

“I am Pratyush. I provide company to companionless people. There is no limit on my time. My fee is two hundred rupees for an hour. I am an educated and compassionate person who will listen to you patiently. You will enjoy my company. I shall accompany you to restaurants and even to your doctor, but if you ask me to accompany you in any illegal work, I shall stay away from it. Even if you want to visit a brothel, I can take you there. If you read a story, I shall be an avid listener, or vice versa. If you want to listen to music, I shall select the most melodious songs for your enjoyment. If you would like to sing yourself, you will find the most attentive listener in me. It will be like this all the way. Now, tell me what you require.”

Diparun Bhattacharya’s Fifty Years Later foregrounds the moral dilemmas of ordinary people during wartime, when survival and ethics collide.

But during the war, neither the good times nor the bad lasted for long. Last night, when the Mukti Bahini attacked the house, Mangla was lying in the storeroom. A gunfight broke out between the military and the Mukti Bahini. Mangla did not know who survived or died. Hearing the sound of gunfire, he ran toward the backfield in the darkness of the night with two cows and their calves. Then, pretending to be grazing the cows, he walked a little through the field and swam the rest of the way to Brahmandanga. The cows were now tired and bellowing loudly. Evidently, their bodies were exhausted due to the fatigue of the journey.

Subimal Babu became distraught on hearing Mangla’s account.

He shook his head and said, “Why did you come here, Mangla? All of us will die now!”

However, his wife was not affected by his worry or his words. She was overjoyed to have received two milk-producing cows.

She stroked their throats with her hand and said, “Now, the children will be able to drink some milk at least.”

Niharul Islam’s About Barek explores love through the lens of what society often labels as ‘madness’. The story questions narrow medicalised definitions, suggesting that emotional intensity and eccentricity may be forms of knowledge and love, not just pathology. The unexpected closure of the story lingers long after reading. Purba Kumar’s Chikankatha poignantly depicts the fading away of traditional art forms and, with them, livelihoods and joy. As craft traditions erode, people must adapt to new ways of survival, often at great personal cost. In Pythias’ Letter by Suddhendu Chakraborty, Sulekha encounters a book about Aristotle’s daughter, and through it, glimpses an intellectual lineage denied to women. The story captures how art and literature can awaken the spirit, breaking open the chains of expectation.

Dear Father,

My previous husband was useless—worthless both in bed and outside it. Instead, I can see Spartan aggression in Procles. You men easily push me towards monotony—the same old things—betrayal, politics, and strategy. Well, Father, you and Mother both discovered the reproductive organ of the octopus – ‘hectocotylus.’ So why was only your name listed as the discoverer in Alexander’s records?

Sulekha read intently. The great philosopher who saw women merely as instruments for childbirth had a wife who was his companion in intellectual pursuits. Like his mentor Plato, Aristotle believed women should have no constitutional or political rights because they were inferior. Yet, without that woman, would Aristotle himself have understood the profound theories of biology? As Sulekha flipped through the pages of Akhtar’s book, she came across the philosopher’s daughter, Pythias, writing elsewhere.

Sulekha’s encounter with Pythias becomes transformative. The story reminds us that revolutions of the spirit can begin simply by reading a book. Sukanto Gangopadhyay’s Transformation examines identity and sexuality as spaces of both self-discovery and struggle. While people may not choose their identities, they continually negotiate how to inhabit or resist them.

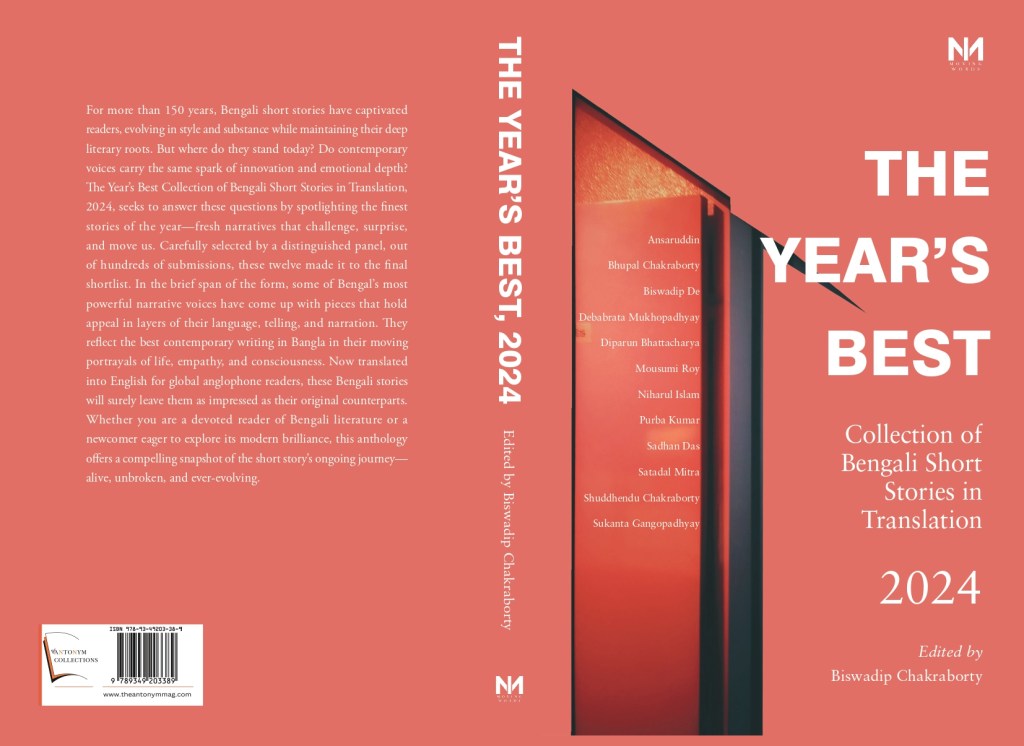

Beautifully edited by Biswadip Chakraborty, this anthology delves into the human condition across shifting timelines, ultimately revealing how little changes at its core. Emotions may alter shape, but dreams of freedom and better lives endure. Despair and loneliness may threaten to overwhelm, yet the soul continues to grow, straining against confinement. These stories, through their finely drawn characters and layered emotions, remind us of what it means to be human: fragile, searching, and profoundly alive.

Additional Infomation:

Title: The Year’s Best: Collection of Bengali Short Stories in Translation, 2024

Editor: Biswadip Chakraborty

Publisher: Moving Words, The Antonym Collections

Year: 2025

Pages: 214

Price: Rs. 449

ISBN: 978-93-49203-38-9

Semeen Ali has four books of poetry to her credit. Her works have featured in several national and international journals as well as anthologies. She has been invited to literary

festivals to read from her works. She has co-edited four anthologies of poetry/prose that have been published nationally and internationally. Apart from reviewing books for prestigious journals, she is also the Fiction and the Poetry editor for the literary journal Muse India.

Leave a comment