Fugitive Friendships— Juhi Saklani

In a ghazal, nostalgic for days gone by, Faiz Ahmad Faiz had written:

“There was an abundance of friends, but we didn’t mind opponents either,

Once we got together, even enemies enjoyed each other’s company”.

That beautifully large-hearted last line – “Jab mil baithe to dushman ka bhi saath gavaara guzre tha” – invokes the rich notion of “mil baithna”. This literally means sitting together, but is redolent of long chat sessions, friendly banter, intense discussions and disagreements. The Bengali adda usually takes place over hot beverages and its north Indian counterpart unfolds passionately in India Coffee Houses in Allahabad or Shimla. In Banaras, the Assi Ghat was celebrated for its intellectual thrust-and-parry conducted in the choicest vulgar slang over tea. But the Hindustani ‘baithna’ among men is a more intoxicating notion. In the film Khosla ka Ghosla, the nouveau riche builder (Boman Irani), fascinated by the sophisticated Sethi (Navin Nishchal), is reduced to shaking his head and saying: “Sethi Saab, aap ke saath baithna hai”. He is foreseeing a session of liquor-induced wisdom, confidences and rapport.

In contemporary metropolitan life – no local tea shop to hang about in, not much by way of leisurely evenings that can be spontaneously devoted to friends, that is, no fursat – get-togethers often mean complicated arrangements of weekends planned well in advance. How to hear the call of ‘mil baithna’ in urban life? Especially for a woman? At least women are a part of the indoor gatherings at homes or in eateries. Otherwise, the Calcutta adda, the Kerala toddy shop where friends meet up, or the UP dhaba where men argue over the news in a shared newspaper, have all been a locus of male activity.

In India’s small towns, sometimes, women neighbours sit on their doorsteps and gossip while shelling peas, and sometimes in cities they pull their chairs towards the winter sun and gather for a chat session. But always close to home. I remember the brilliant initiative ‘Why Loiter’ which brought together women who went for regular aimless walks at unusual times in an act of reclaiming their city. The only time I personally experienced the possibility of sitting and vociferously engaging in a group in public was in the dhabas of my university, JNU.

All of which is to say that the idea of being outdoors, engaged with friends or strangers, enjoying each other’s company, has a powerful pull for me and is responsible for much of the flânerie in my life. I have spent years walking about the streets of Delhi, stopping to chat with shop assistants, beggar children, security guards, paan walas, fruit sellers… . I bond with people as we wipe sweat from our foreheads and shake our heads at the heat; with people holding lovable infants; with homeless people who feed dogs; with people who compliment me on not colouring my hair while I encourage them to stop colouring. There are shared smiles, witticisms, compassion, little windows into each other’s being. I know the details of the lives of many taxi drivers. The magazine seller knows of my wish to live in the Himalayas. The gym owner and I share a love for, and many stories of, tigers. The trekking guide tells me why he doesn’t want to marry. That is, I experience life as a string of ephemeral ‘mil-baithna’ possibilities that our times offer to us.

An Alternative Pather Panchali

When I get into the taxi, the Uber driver returns my greeting with added gusto. It is past 9.30, he says, so we will face no jams on this route. I tell him that I had been sitting in a cafe for an hour precisely because I wanted to skip the heavy traffic. “I also had coffee!”, he exclaims with delight. “For the same reason! I often take an hour out in the peak hours to just hang around, having coffee or some snack. The money I’d have earned by driving at this time is not worth it.” We beam at each other in the mutual joy of recognition.

We are now a tribe of two, feeling validated by, and aglow in, each other’s voluntary ‘wastage’ of time to opt out of peak hour rush and a mutual liking for coffee. When I leave the taxi, we know each other’s ethnic backgrounds, what our native places are like, why we came to Delhi, what his children are doing. We will never see each other again. But would it not be possible to include our interlude in the capacious being of friendship?

At one point, my Facebook friends simply stopped believing that my stories of bonding with taxi drivers over music were true. It was Covid time and I would regularly travel between Delhi and Dehradun where my infirm father waited for my visits. It all began with Bunty bhaiya, who had a pen drive of old Rafi and Lata songs that Saregama could learn from. When ‘Wo jab yaad aaye’ started playing I cheered up and nodded appreciatively through the song. When ‘Likhe jo khat tujhe’ began, I could hear him humming as I could hear myself humming, both of us shy. By the fourth song (‘Wo hain zaraa, khafa khafa’ for the record), we were warbling lustily through our masks and sang our way through the entire journey.

Bhushan ji played Talat Mahmood (“In gaanon se, shaanti si aati hai” which roughly translates to, There is a peace that descends with these songs)), told me that his daughter was learning French, and gave gracefully assent to his favourite Deluxe thali that I would always offer him at our midway stop, Cheetal restaurant. I have stopped at Cheetal for 55 years of Delhi-Dehradun travels and the waiters there usually welcome me like a married daughter returning to her natal home. But my closest friend in Cheetal is Kavita.

Kavita is responsible for keeping the women’s loo clean. For some years now, I have met her for a few minutes, every few months. She is a widow with two children but her father managed to buy her some land near his house in the village, so she lives independently. She likes this arrangement. The restaurant van drops her home. She enjoys meeting the diversity of women who come to the loo.

Because I travel alone and wear no jewellery at all, Kavita had assumed I was a widow. One day, she said lovingly, “Find a man for yourself. As long as it is a good person, it is ok to be with someone. Don’t worry about what people will say”. I am deeply touched by her concern and sensible advice. I explain that I do have someone and he is a very good person. She is all smiles, as if truly relieved that she need not worry about my well being any more.

At the peak of Covid, in a deserted bathroom, I had heard Kavita humming beautifully. “My father loves old songs; I was always surrounded by them”, she said. “When all this is over I will record your voice”, I declared. So last year, on a day when the loo was empty, I reminded her of our plan. She looked around surreptitiously and bolted the main door. Then, under the tall ceiling of the closed bathroom, with the sound exquisitely resonant, she sang ‘Do lafzon ki hai’. When I hear the song in Delhi, her sweet high-pitched voice and my appreciative humming mingle and create misty echoes in the room.

The Human Continent

Kavita reminds me of Amma – plump, smiling, name tattooed on her forearm – who used to collect the garbage from my rented flat decades back. On a sweltering Sunday morning, as she accepted a glass of water, for once she took up my offer of sitting in front of the cooler for a while. Since she refused to sit on a chair, I sat on the floor with her and asked her about her life. What followed was most unexpected. It felt as if a flute was playing among those DDA flats. As far as I could see, everything was very nice. She lived close by, her son lived in the adjacent house, her daughter-in-law was very nice, her grandchildren insisted on sleeping with their grandmother at night, her daughter was married to a nice man, her neighbours were very nice, everyone called her Amma… . Amma has been enshrined in my heart for the last 25 years as my personal deity of dignity, sweetness and content.

Much like this interaction with Amma, I find joy, affinity, playfulness, strength in the most unlikely places. At the first question about their name, the children selling pens at red lights give up their impressively pathetic expressions. A couple of exchanges more and they giggle and suggest that I feed them chowmein. I tease the night duty watchman in Connaught Place: “Reading the newspaper this late?” “If I’m reading the news for the first time it’s fresh for me, no?” he laughs. The office peon standing motionless in a patch of the winter sun doesn’t want to return indoors. Last year, back in Gorakhpur, he missed out on clearing the entrance exam for a police constable’s post because his family couldn’t afford the money to buy the question paper. But he laughs and puts a brave front on it. The elderly gatekeeper of York Hotel explains sincerely why he has been standing on one leg. He takes the name of Ram 50 times and then changes legs. That way, both legs don’t hurt simultaneously. My heart breaks, but he is more interested that I should appreciate his solution. Late at night, two thin young men from Daryaganj are driving a tiny battery scooter down the Connaught Place corridors. They belonged to a merry gang of five, but two of the girls got married (“and who will allow them to join us now?”) and a boy shifted out of town for a job. They miss their friends, they say, and look miserable. The paan-shop owner in front of Odeon minds a deserted stall during Covid. He consoles me: when the good days didn’t last, why will the bad days last?

Each person, a continent of unimaginable narratives, emotions, thoughts and desires. Each encounter, simultaneously personal, political, spiritual. Human, defenceless, open.

The Ones who Pray for Us

Of all my ephemeral friends, the one I remember most, the one with whom there was true ‘mil-baithna’, was Ritu. On a hot afternoon in Connaught Place, I came across her, obviously badly damaged by acid. I asked if she wanted water and would she be able to drink with a bottle (she didn’t seem to have lips). “Yes, easily”, she said. So I got her a bottle. “You drink too”, she suggested. “You and I can both have it when it’s cold. If only I drink, the rest will just sit there and get warm”. I was very pleased with this sharing of coldness in summer, so I sat down next to her to chat. The conversation that followed covered many things, but the one thing it did not dwell on was her misfortune or suffering. Half an hour into the chat a gentleman stopped by and asked me in English, “how did this happen to her”, and I realised that I didn’t know. She had helped me get over the obvious; she was much (much!) more than her disfigurement and living conditions.

We bonded over films. She lived at New Delhi railway station and saw films at Shiela cinema nearby. The film she had remembered all her life was Sadma. “I felt so bad about the ending that I got a fever!” I completely agree. Sadma had been traumatic for the teenager I was when I saw it. We shook our heads in wonder at Kamal Haasan’s acting. But guess what was even worse than Sadma? Titanic! It should have had a different ending! She needed to drink for her pain and now liked drinking very much. How often do you drink? She winked with a non-existent eye and giggled “Don’t ask”.

The next time we met, I asked Ritu if she wanted treatment or anything else. But she declared she was content: The police sir here is very goodhearted. I have a bit in a bank account that a nice lady opened for me. If anybody needs, I give with all my heart. Just that I am a drunkard”, she said, laughing. She only wanted one thing. She used to beg with an old man, but now he was ill. The only wish of this acid-damaged ‘beggar’ was that the old man became better.

As I started to get up she said she wanted to give me something. Then she cupped her hands, blew on them with her non-lips, and poured the air on my head in blessing.

After three meetings, I never saw Ritu again and nobody from around her chosen spot could tell me about her. As if to make up for the sadness and worry, Santara came into my life. Crippled by Polio, Santara has the sweetest smile imaginable. When I first met hecar she was very pleased that she had managed to get a self-propelled wheelchair from the Delhi government. She had joined a church and now could visit it when she liked. Next time, she showed me the WhatsApp sermons which she hears before sleeping. Echoing the taxi driver who heard Talat Mahmood songs, she says they give her a lot of “shaanti”. I hold her hand as I leave. She says she will pray for me tonight.

A Little Boat

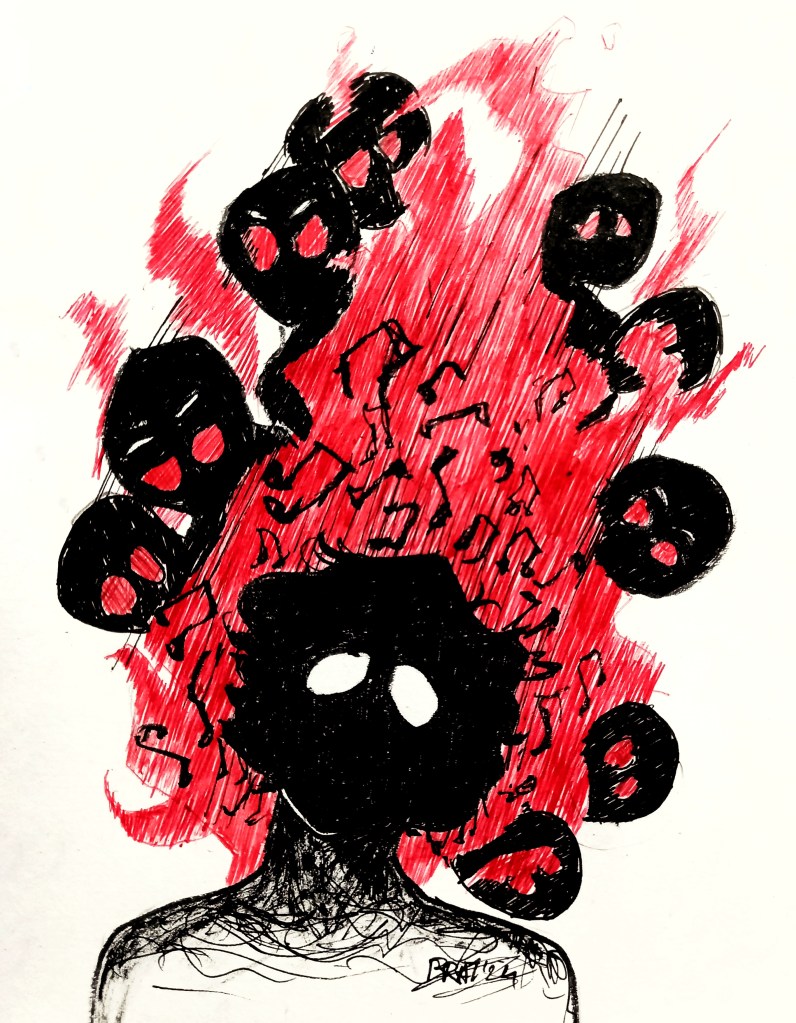

This possibility of fugitive friendships appears to me like a little boat flowing in the midst of the stereotypes of urban life: the alienation, speed, noise, impatience, the stress and the perpetual hurry. The possibility that we stop, relax, engage and enjoy. It travels around the city, finding itself in small courtesies, witticisms, fellow-feeling, shared experiences. There are contingent bonds and playful mutualities, luminous in their own way precisely because ephemeral and not weighed down by roles and agendas.

These moments exist underground, not interrupting the main narrative, always there when wanted. They shine on the possibility of communication and friendship as an act of solidarity, as a liberation from hierarchies, as a politics of the spirit. And they do give us – like Talat Mahmood songs, like Santara’s prayers – an existential shaanti.

Juhi Saklani is a writer, editor and photographer based in Delhi. She has written on art, travel, cinema and contemporary life for several publications, such as The Hindu, Frontline, The Wire, Outlook and Outlook Traveller. She has edited Iti Satyajit Da: Letters to a Friend from Satyajit Ray and the centenary volume Somnath Hore, and has received the India Habitat Centre’s Photosphere fellowship.

Leave a comment