“Jumping With Frogs” by Devashish Makhija

When a frog jumps up into the air it does so from a squatting position. It uses the strength latent in its legs to spring itself into the air. As it springs up its legs stretch in mid air, its body trailing its head like an upward soaring comet’s tail. And then as it falls, its legs stay straight, till it hits the ground feet first. Its knees buckle, the impact of the landing riding like a wave through its little green body. And it folds up as it lands, back into its squatting position – a spring held back down, ready to spring again.

But when humans jump up into the air they do so from a standing position. We use the energy latent in our solar plexus to whip our feet off the ground. And as we rise into the air our knees fold, until they press against our chests in mid air. Frozen up here for a split moment, we appear to be squatting, much like the frog was doing, but in its case on the ground. Then as we fall, our legs unfold till our feet hit the ground, and we’re standing again. Here we appear so static, so stable, so unshifted, as if we never jumped at all.

By this perverse, contentious logic we humans are just the reverse of frogs!

I’ve been a bibliomaniac in my teenage years. That’s the book equivalent of a kleptomaniac. I have done it all. Starting from the relatively non-criminal act of never returning a book I’d borrowed. To wearing a loose shirt to the annual Calcutta Book Fair and walking out of most stalls with a book underneath it. And now I possess so many books that every once in a while, I look upon them as my ball-and-chain shackling me to a materialism I abhor but allow myself to be consumed by. I curse them for being so demanding, promise myself that enough is enough, and that no more books will be acquired henceforth. I will instead spend my money and time acquiring…

acquiring…

acquiring… er, experience!

My disgruntlement with my ‘condition’ reaches mythically self-flagellating proportions during the same particular period roughly every year… when my one year lease as a tenant runs out.

I was shifting house again. My eighth such shift in seven years. I’d spent all night carefully packing my four cupboards’ worth of books in cartons that I had made ‘Alpha packers & movers’ leave behind, not trusting my books to their lack of packaging skills. I’d moved house enough times to know that if I wanted my literature to arrive at the destination in the same condition as it were at the departure point, it was up to me to tuck each tome snugly into the rigid confines of the large cardboard cubes. Fitting the books in that limited geometric space, given that all my books – from modestly sized novels, to limp-cover comics and large multi-kilo volumes on design and art – were of dramatically different dimensions, was a feat that required a balanced mix of physical dexterity, an alert intellect and extreme and controlled emotion. As far as possible the books had to be packed –

a. by subject

b. by the esteem I held them in

c. by size

d. by their hardness or softness

e. their age

I admit it sounds strange but the key to packing books – so that they can withstand, and prevail, a rough and tumble journey in the back of a truck lurching over potholed roads – is ‘breathlessness’. Every last square inch in the carton must be occupied, stuffed with either a book or rolls and wads of newspaper, the space snuffed out, so that the packed books, much like the mummies of ancient Egypt, cannot move. Because to move inside that carton is to submit to a shoving. And when shoved around against the weight of other books a book will lose shape. And a book out of shape is a book with no self esteem (and not much of an after life). If every last book in the carton is not squeezed in tight and intact, there could be a mini hurricane inside. And when the carton is opened in the new house what emerges could be torn, crushed, mangled, loose-spined, crumpled, scattered trash, fit only to be pulped at the book equivalent of a crematorium.

Which is why, as I mentioned before, ‘controlled emotion’ is a key ingredient of this enterprise. In such an endeavour patience is lost easily and far. The bile knocks relentlessly at the base of one’s throat. And the brain, like all cheap laptops, unfailingly ‘hangs’. Because the last thing one wants is a dear book finding itself in the other tray of a pair of weighing scales at the raddiwallah, its value being measured not in rupees but in ‘grams’.

The raddiwallah is a strange phenomenon of Indian life. His shop is usually a small, dingy, musty hovel in the anal cavity of a decrepit building, crammed with other peoples’ memories and the daily recyclable leftovers of their lives.

My earliest memory of a raddiwallah (aside of the thousands of times I have scavenged through heaps of tattered books discarded in their dens) was when a particularly well-fed one had arrived, gunny sacks in tow, to heave all my old toys away. I had recently turned ten. And all the plastic, metal and wooden toy guns I’d gotten (asked for, rather) as gifts had made most of my other toys near redundant. And mom and dad, after many mornings of whispered apprehensive conference, finally told me that they were going. Away.

The last to disappear into the raddiwallah’s sack (which when filled with all the joys of all the afternoons of my entire childhood stood a mere one foot taller than myself) was my most favourite blue and red, large, plastic Boeing airplane. It was my earliest, biggest toy, and it was special because unlike the others it didn’t arrive in a large printed box or smothered in cellophane wrapping. It had an owner before me. A much elder cousin who had since joined the Air Force. The Boeing had a history. It had scratches on its undercarriage from innumerable forced landings even before it was entrusted in my care. I watched it longingly.

But when the sack was nearly stuffed, the soft, fat raddiwallah turned to his helper and snorted, ‘koney mein ddhuka do’. The wiry man grabbed the plane with long wiry fingers, shook it like a rattle to check for loose parts and was about to stab it nose first into the corner of the sack, when I gasped in shock. He heard me, smirked, stopped the vertical descent in mid air, made plane sounds, pretending to make the Boeing take off again, swooped it around in a figure of eight and made it nose-dive into the sack with a soft plastic crunch!

So I ended this, my third consecutive night of book-packing, at 5 in the morning, with a sore back, throbbing arms and a living room that resembled the surface of the sea one minute after a shipwreck.

The tally stood at 44 cartons.

I awoke at noon to a SMS from F… ‘A pest control guy came by our house this morning to ask if the pigeons were being a nuisance, and I wondered if the pigeons thought the same of us.’

I read that message over and over, the guttural chirping of the pigeons outside my window gradually drowning out the whiplash rumbling of my cheap ceiling fan. I turned on my back to digest the thought, when I groaned in pain, and remembered what I’d been up to all night. I wondered if the pigeons outside had watched me quietly from the darkness, and were discussing the cyclic pointlessness of my life.

Take books off shelves.

Pack books.

Shift house.

Unpack books.

Put books on shelves.

Take books off shelves.

Pack books.

Shift house.

Unpack books.

Put books on shelves.

Take books off shelves.

Pack books.

Shift house.

Unpack books.

Put books on shelves.

You get the drift.

I wondered if they wondered why we cut their homes down to build homes for ourselves, then stuff our homes with things we’d mostly never need, then get ourselves more and more of such things, and cut more of their homes down to make room for these things, which mostly made us unhappy with the effort it took to look after them.

I remembered pushing a crow’s nest off my bathroom window ledge some months back. I’d grimaced at the bird shit that it had wrought.

I wonder now if the crow had a bright blue clip it had stolen from someone’s clothesline. And what if it had a shining metal hanger too, that it had used to prop up its nest? What if it had stolen several clips? Perhaps like me, it was a ‘clip-tomaniac’. What if it had just shifted to my window ledge after being asked to leave the tree that was cut to broaden Yari road? What if, unable to find an alternative tree, it too had spent a whole day shifting its clip collection to its new home here. Exhausted it had flown off to find a bite to eat and was harbouring dreams of finally resting its aching wings. Only to come back and see me push the nest off the ledge with a broom-stick.

I wonder now how I’d feel if someone who found me a nuisance simply threw all my cartons of books out from my third-floor window onto the rain soaked ground below. The thought sends an ugly shiver up my spine and I leap out of bed and dash to the living room. The shipwreck is exactly as it was at 5 this morning. I am not yet a crow. At least not in the current scheme of things.

But if the pigeons and crows decide that enough is enough and the world is indeed a shared commodity, despite what humans might think, I just might find myself at the wrong end of the broom-stick.

Standing there, my last day in this house, surveying my endless cartons of ‘stuff’, I think of the one sustained aspiration I’ve had ever since I moved to Bombay… of owning a bike. I think of the day I will ride out of the showroom with it. And then I realise that like all good stories, it will not be the end, but merely a new beginning. Because soon I will need –

- a plastic cover to protect it from the rains

- gloves

- a helmet

- seat sleeves

- a servicing contract

- a raincoat (since the umbrella was invented, in my humble opinion, long before the wheel was, hence making the two ergonomically incompatible)

- regular visits to the petrol pump

- a loving (!!) bike-wash every sunday

- heartburn in every traffic jam

- …and I decide to drop the idea like a steaming potato.

I’m better off, I tell myself, being at the mercy of erratic public transport and letting my sex appeal take a hit. At least once I’m in the auto / taxi / bus / train what transpires en route is not my responsibility.

Even one less responsibility in a life splitting at the seams with them is welcome relief.

For now though, despite being stunned into existential re-evaluation by F’s SMS and the displaced crow’s plight, I can’t imagine my books not moving house with me. So, I decide instead to sacrifice my next planned acquisition – the bike. All the 500 cc, throbbing, gleaming black sexiness of it. The shedding of my urban-consumerist-all-too-human condition can only happen one day at a time. I’m unprepared yet for an all-at-once upheaval. I murmur a small apology to the absentee crow and tell him that he can return to the ledge. His tormentor has been served his just dues. For now.

A sticker I owned as a child stayed unused, pressed safe between the brittle pages of ‘The Blue Lotus’ for nearly fifteen years. I discovered it serendipitously the day I carted my Tintin collection to Bombay, when it quietly slipped out of the book and fluttered to the floor. It had stayed unused till the day when it would truly find its vocation – a place of pride on the glass window of my precious book case. I finally peeled it off its waxed paper base and squelched it onto the glass. On it were two playful frogs. Frog #1 squatted in the left corner. Frog #2, in the right corner, was sprung in the air. In between them was the legend in a playful froggy green – ‘Keep Bombay green. Grow more frogs.’

The suggestion rang with a deeper, more profound truth today. The mangroves that are now Bombay must have once been home to more frogs than humans. But just like the crows and the pigeons, we quickly and systematically drove them all out of their home too, to occupy it ourselves. And one of these marauders decided to put a little quirky sticker on his book shelf window as a funny but hugely tragic tribute to what was, what should have been and what probably will never ever be.

It’s what makes us jump so differently from frogs. Our hearts, minds and eyes are too far above the ground we walk on. And we choose not to see what gets squashed beneath our feet.

Today I feel like a pest. Something that merits eradication. With a two-year contract perhaps, renewable. So that the pest controllers can return periodically to ensure no recurrence of an infestation. I want to be sprayed with the mosquito’s version of ‘human baygon’. Baited with pizza laced with poison, placed in the corner of a large human-trap.

Or perhaps, feeling useless, I want to be sold. The raddiwallah seems like a rehab centre for all things past their utility date. An orphanage where dispossessed children seek new ownership. A transit room between one life and the next. Perhaps I want to be shoved in a gunny sack and carried there to disintegrate in an airless corner of his shop.

Perhaps.

Romantic existential claptrap. Since I’m now cramping with hunger. Shuffling to the kitchen I see that the two eager pigeons who unfailingly fly into my kitchen to er, doobie atop my dish rack are back. The male (presumably), clawing his way onto his partner’s back, stops when he sees me, and slides back down. I always shoo them away. They wait. I watch.

I think of frogs.

I think of crows.

Of pest controllers.

Of raddiwallahs.

Of missing trees.

And the bodies that burn in those trees’ chopped remains in crematoriums.

I think of bodies.

I think of an egg.

I feel hungry.

But then I think of the little pigeon hatching from that egg.

And I quietly turn about and exit the kitchen.

I hear a squawk behind me as I leave.

Doobie doobie do, pigeons, doobie doobie do.

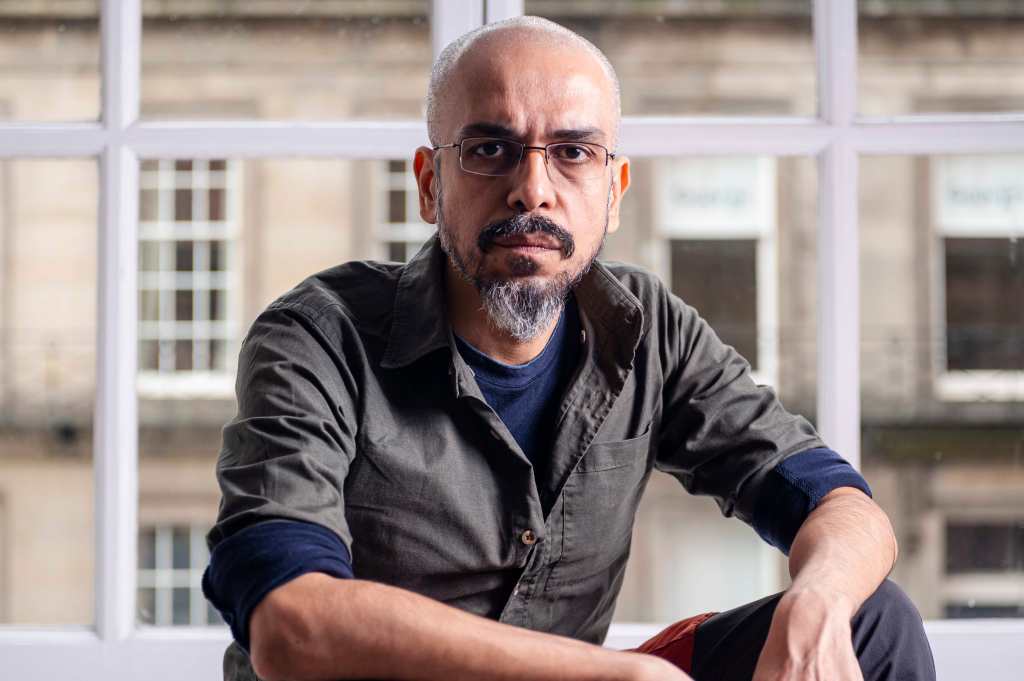

Devashish Makhija has written the award-winning novel Oonga; the collection of short-stories Forgetting; two poetry collections Occupying Silence and Bewilderness; several picture books for children; the international, National and

Filmfare award-winning films Joram, Bhonsle, Ajji, and several widely-acclaimed short films.

Leave a comment