Mehak Jamal talks of creating a “a repository of undeniability“

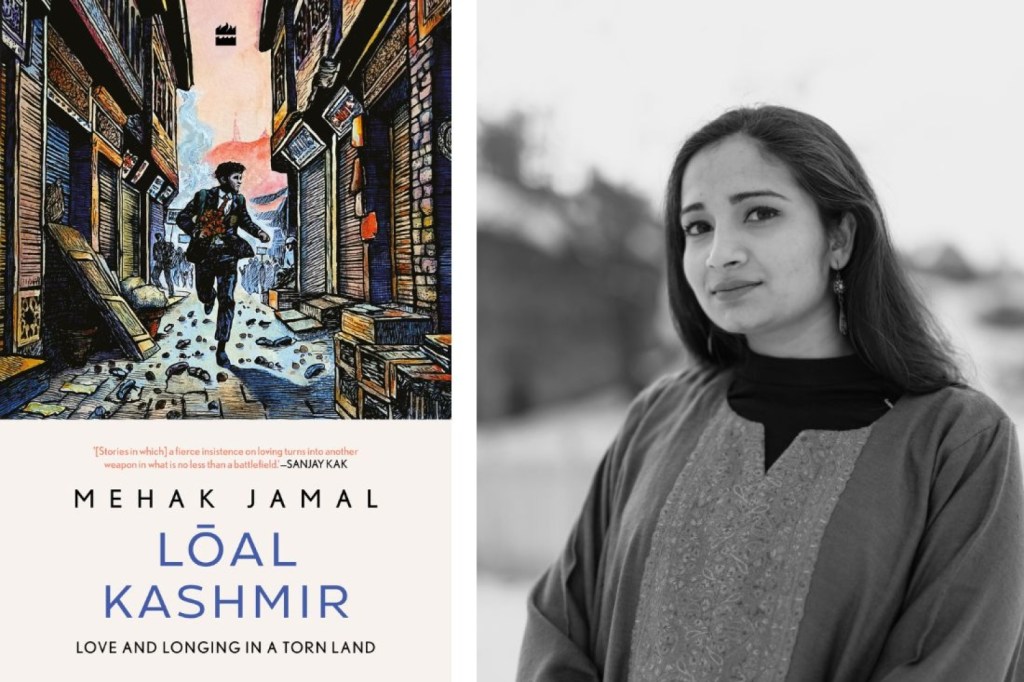

Mehak Jamal’s debut work Loal Kashmir: Love and Longing in a Torn Land has been the talk of the literary world since its publication. Sayan Aich Bhowmik was in conversation with the author, trying to dig deeper into what went into the mapping of the book, the reception that it has received and her future plans. Read On…….

S.A.B– Firstly, let me congratulate you on your book. It has struck a chord with the readers, across different age groups. How have been some of the reactions that you have received as an author? And, when you were starting out to write Lōal Kashmir, did you guess or hope that the response would be so overwhelming?

M.J– Thank you very much. The response has been warm and kind. People are resonating with the material, and many Kashmiris are relating with what’s happening in the book, the latter often reaching out to tell me the same. That was the intention of Lōal Kashmir and I am glad that I was able to achieve it. The response to Lōal Kashmir when I was collecting the stories was overwhelming back then, so I was wishing that when it releases, it elicits a similar one. And I was not disappointed. I am humbled with the love it is receiving. I hope that it reaches even more people, and continues to be found and read.

S.A.B– What prompted you to undertake this journey? I ask this because, when we read fiction/non-fiction/ poetry from Kashmir, the focus is generally on the political/social crises and the very problematic relationship with the Indian Government, and perhaps rightfully so. Was there a moment or incident that acted as a catalyst that made you want to write about love stories and their struggles from Kashmir?

M.J– As you rightly said, the Kashmir conflict is the focus in much of the texts on Kashmir, and it should be rightly so. It needs to be well documented and cemented in history. I had noticed that initially this was often documented from an academic or journalistic lens. It is only in the last 10-15 years that writings from Kashmir (by Kashmiris) that talk about the lived memory of the conflict have started coming up. For the longest time, the books on Kashmir were written by non-Kashmiris. Reclaiming this space by Kashmiri writers is a powerful tool to document and preserve history, memory, and perspectives. I personally wanted to collect and give a voice to these narratives for a few different reasons. The simplest one was that I hadn’t myself read such stories of love and longing from Kashmir, and this curiosity fuelled me to discover them. Secondly, having grown up in Kashmir and having gone through many periods of civil unrest myself, I was always curious about the documentation of the lived experiences of the unrest—of how Kashmiris live, love, and go on. How collective public memory is shaped by the conflict is as imperative to document as the facts and figures themselves.

The final blow so to speak came in 2019 with the abrogation of Articles 370 & 35A. When the unprecedented communication blockade went on for months without any respite in sight, it got me thinking particularly about what such a period would do to the lovers and loved ones in Kashmir. I started this inquiry a year later in 2020, and was startled to see how many people wanted to share their stories of lōal through different periods of unrest in Kashmir. This wasn’t limited to romantic love only, but spoke of other kinds of love as well. What started as a quest to preserve these memories of love and longing through the conflict, became a book four years later.

S.A.B– Your accounts are a testimony to the everlasting power of love– some finding fruition and some unrequited. Going through them one cannot but recall Shakespeare’s, ” The Course of true love never did run smooth.” How was the experience of interviewing some of the people whose stories feature in the book?

M.J– It has certainly been a cathartic experience interviewing the contributors and bringing their stories to the world. While some stories have happy endings, many do not, and some end in a bittersweet manner. The stories traverse a 30–40-year time period from the 1990s to 2020s, and each story is emblematic of the time that it’s from. But what is interesting is that though so much changes and evolves in Kashmir during the course of the stories unfolding, much remains the same because of the enduring conflict in the valley. While in the first chapter, in the 1990s, Javed and his girlfriend write letters to each other as not many forms of communication are available to them, some 30 years later in 2019, Khawar and Iqra resort to letter-writing because they are left with no other means of communication in an advanced technology driven world. This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the narratives in the book, each exploring a facet of love and life in Kashmir, which is so informed by the conflict itself, yet at the same time finds its own place and face in the midst of it.

S.A.B– If we go back a little, to your growing up years, who were your literary influences? Authors and poets who made you want to pick up the pen and experience the thrill of telling a story?

M.J– My early reading pretty much took the general trajectory one takes, from lots of Enid Blyton, Harry Potter, Lemony Snicket and the literary classics, etc. I moved onto Anne Frank, The Catcher in the Rye, To Kill a Mockingbird etc. in my mid-teens. I discovered Agha Shahid Ali in my late teens who really solidified what it is to write about Kashmir and create an evocative picture of the place and the yearnings of its people. I don’t know what made me want to tell stories as such, especially as a book. I think my main inspiration for storytelling has always been film. I was drawn to film making and world cinema in college. I discovered Iranian, Polish, French, Spanish etc. films and never looked back. Even today when I think of a story, I look at it as a film first. Lōal Kashmir started in my head without a form. Though the initial ideas circled around filmmaking, the sheer quantity of the stories I had compelled me to venture into making them into a book.

S.A.B– In the book’s dedication, you also talk of being provided with the latest books to read while growing up. Could you talk a little bit about the cultural atmosphere in your family/ household during your formative years.

M.J– My mother was an English teacher in my school and my maternal grandmother would buy us dozens of books each year. I owe a lot of my reading prowess to them, and my elder sister who was a bookworm much before me. We were encouraged to read at home, though I started quite late. I couldn’t get myself to sit still and read anything for a very long time. That is until I got measles when I was 9. I was quarantined in a room and it incidentally had our childhood library as well. That’s when the reading bug caught me.

S.A.B– In the last twenty years or so, there has been a lot of focus on the literature emerging from Kashmir. The likes of Basharat Peer, Shakoor Rather, Rahul Pandita and recently Zahid Rafiq have all added their distinguished voices to the canon of Indian Writing in English. Do you feel that this exposure was long overdue? What are your views on the way in which the rest of India is getting to know about Kashmir, its problems and people beyond the mostly half-baked cinematic representations in Bollywood in the past and the very official historiography that is put out by the national media?

M.J– It is certainly long overdue. As I mentioned earlier, for a long time, books on Kashmir (in English) were being written by non-Kashmiris. I don’t want to get into the content of the books, as many of them are important books which were much needed. But to document a place and a people, the art and literature needs to be carried forward by the indigenous inhabitants. The narratives written by the above that you mention and many others like Farah Bashir, Feroz Rather, Mirza Waheed etc. help create a picture of Kashmir that would otherwise fall through the cracks and never be seen, just because it isn’t ‘news’ or it ‘is not important enough’. When you look at any historical tragedy in the world, the people who have gone through them are thoroughly interviewed. This is to make sure everything is documented for the future generations to see, and to make what they’ve gone through ‘undeniable’. The perception of Kashmir in popular news & media has been and still is very black and white, with little room for authenticity and nuance; often relying on eye-catching headlines and not much else. When more voices from Kashmir tell their own stories, we not only set the narrative right, we cement our place in our own history (and memory), which is written and told by us.

S.A.B– Coming back to your book, it is much more than just couples in love struggling with and negotiating with a society in crisis, especially after the abrogation of Article 370, but the narrative also provides a sharp insight into the social and familial fabric of Kashmir. The way gender roles are seen and performed, how at times the word of the male family member is the last word in matters of familial and marital significance– could you please elaborate a little on that?

M.J– When you talk about any society, the various social dynamics at play come to the fore. What I noticed in some of the stories in my book was how much agency the women showed, particularly in love—something that was often lacking in other areas of their life due to familial pressures and restrictions. In a place like Kashmir, women often aren’t able to inhabit many physical spaces that the men do, due to societal norms or due to the level of danger at that moment. But when it comes to love, women often go above and beyond to show their love to their significant other. If you take the last chapter of the book ‘Agli Hartal’, Nadiya has many pressures from her family and has lived a sheltered life where her strict father’s word is always final. She has been with Shahid for almost a decade and when her family starts looking for grooms for her, she is certain that she won’t marry anyone else but Shahid, even if the family pressure goes above and beyond. She keeps getting degree after degree to slow down the marriage prospects and waits for Shahid to become independent in his business, all the while thwarting marriage offers. This dynamic is not unknown in South Asian communities, but Nadiya does this even though her father is a looming, authoritative figure in her life who she has never locked horns with for anything else she wanted, but she does it unabashedly when it comes to love. It’s really fascinating to see.

S.A.B– You have been a film-maker and have been writing for the OTT platforms, having co-written Love Hostel and the web-series Never Kiss Your Best Friend. What is the difference in the kind of thrill and satisfaction that you get from writing/ working on a film and a book?

M.J– They are two very different beasts. Also since screenwriting is the blueprint for the final product which is the film or the show, it cannot be made in a vacuum. You need a village to make the film. Writing a book is more of a solitary process, plus it is the final outcome of all your efforts. Both take the time that they take, but at the end of the day, I feel you may have more ownership over a book than you do over a film, even if you are the director of said film.

S.A.B– Reading Lōal Kashmir, I was struck by how some of the stories have great cinematic possibilities. In the future, can we expect you to consider writing/ making a film on Kashmir and its people?

M.J– Certainly, that is the hope and the dream. I want to tell many more stories from Kashmir, especially as films. At the same time, I don’t want Kashmir to be the only topic I talk about through my stories. As Agha Shahid Ali famously said, ‘If you are from a difficult place and that’s all you have to write about, then you should stop writing.’ This quote reflects his belief that while his poetry frequently dealt with the political turmoil and violence in Kashmir, he felt an artist should not be defined solely by their origins or the troubles of their homeland. It highlights the need for artistic depth and exploration beyond mere representation of difficult circumstances. I want to achieve this balance in my work.

S.A.B– In a world which is increasingly in the grip of a kind of animosity and impatience to acknowledge religious/ cultural and social diversity, I feel the need of the hour is for more storytellers to step forward, to create a kind of repository for narratives that will challenge and present a counter discourse to the more overarching and enveloping official and majoritarian accounts. Do you acknowledge that authors have a greater responsibility now, that their silence and words both have a greater ramification in the destiny of a society and how the next generation will shape up going forward.

M.J– Yes, I continuously think that when we speak about, write about or document history, there is a great need to document memory and oral histories as well—to create a repository of undeniability. That was my intention with Lōal Kashmir as well. In the world where we live in, when facts can be altered, histories can be erased, the arts are a great way to circumvent this. Books, films, music and media etc. are a great tool of soft power when it comes to documenting narratives for the future generations and public consumption. I think we all have a collective responsibility to do this, as silence is often no less than complicity.

S.A.B– Thank you so much Mahek. For your candidness, and for taking time out from your very busy schedule. May the book reach more people and may love triumph. Everywhere…

Mehak Jamal is a filmmaker and writer. She was born and raised in Srinagar, Kashmir, and has always wanted to tell stories from her homeland. Mehak likes to subvert stereotypes and explore shades of grey through the stories she tells, be it in film or books. Mehak is a 2022 South Asia Speaks Fellow, awarded to outstanding emerging writers from the region. Her film Bad Egg premiered at the 19th Indian Film Festival Stuttgart and won the Audience Award. It went on to screen and win awards at multiple film festivals all over the world including Melbourne, Madrid, Chicago, Atlanta, Washington DC, Kerala and Dharamshala, etc. Lōal Kashmir – Love and Longing in a Torn Land’ is her first book. It was published by Fourth Estate, an imprint of HarperCollins India in 2025. Lōal Kashmir is a rare collection of sixteen real-life stories of love, longing and loss from Kashmir, a region that has witnessed decades of conflict. Mehak is a film alumna of Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bengaluru. She lives in Mumbai with her cat, Ellie.

Sayan Aich Bhowmik is currently Assistant Professor, Department of English, Shirakole College. He writes poetry, reviews books and is the founding editor of Parcham.

Leave a comment