From Trivandrum Cntl. to Bhopal Jn. by Anu Susan Abraham

Two pairs of clothes, one towel, one Yardley Talcum powder, seventh standard English and Mathematics notebooks, one pencil box, a few Indian rupee notes and the school uniform that they changed just before stepping onto the sleeper compartment of Kerala Express 12626 travelling from Trivandrum central to New Delhi, were the only things they had in their school bags. Both had a frail constitution. You could count the ribs on their little chests under their shirts. Vishnu’s face was like the shape of the Little Hearts biscuit they bought to eat on their way. He looked as sweet as the tiny white sugar dots on Little Hearts. Aju looked like a frightened fish washed onto the shores by a harsh wave. Unlike Vishnu, who wore a fancy yellow t-shirt, grey baggy jeans, and red-rimmed plastic glasses, Aju wore his usual oversized blue chequered shirt inherited from his elder brother Tiju and the black school uniform trousers. Both sat together, leaning onto a window seat. Vishnu’s right hand was laid comfortably on Aju’s shoulders like a mother hen’s wings over its chicks.

As the wind caressed their foreheads, a wide yawn passed through Vishnu’s mouth and knocked on Aju’s lips. Aju’s lips welcomed it without any further concern. The rhythmic lullaby of the train felt like their mother’s tap tap on their backs at night after putting them in bed. The Little Fish and the Little Heart slowly glided into their sweet dreams, though Aju’s dream was not that sweet. Aju saw his mother calling him from the other side of the road. Aju wanted to rush into his mother’s arms, but the road suddenly filled with effervescent blue waves, and bloodthirsty sharks emerged from it. One even tried to catch him. He ran in panic but stumbled upon a rock and fell into a nearby well. Before his head smashed into the waterless well’s rocky bottom, he woke up and saw the TTR coming. Aju pulled on Vishnu’s t-shirt to wake him up from his daydream. Startled by the force of Aju’s pull, Vishnu woke up.

“Destroyed! I was on a beach relaxing on a deck chair under the rainbow umbrella”. “You destroyed it, man”. Vishnu said.

Aju whispered into Vishnu’s ears, “See who is coming!”

When Vishnu saw the TTR coming, he held Aju’s left hand on his right hand, grabbed their bags with his left hand, and hurried towards the lavatory.

Vishnu spread the Yardley powder on the toilet seat and the corners of the lavatory.

“See, this is why I told you to take the talcum powder. Understood? Otherwise, we would have died inhaling this stench of other’s pee and poop.”

Aju put his palm on Vishnu’s mouth and gestured to him not to make a sound.

For around twenty minutes, they stayed like that in the lavatory. Vishnu opened the door and cocked his head to see whether there was anyone outside. Once he understood that there was no one, he immediately jumped outside and asked Aju to follow him. They spent two days on the train like this, running from one compartment to the other and sitting inside the lavatory in pin-drop silent mode. After two days, they decided to get down at the next station when the biscuits were over, and their ribs became more visible under their shirts. By then, the train had taken them thousands of kilometres away from their hometown in Kerala. The train carried them across the slender, crisscross form of the Nila River and through the semi-arid dry lands of Tamil Nadu. The smell of the hot winds of Erode was a strange mix of turmeric, fresh Jasmin flowers and idli-vada wrapped in banana leaves. Aju and Vishnu smelled the Tirupati prasad on the dothis, knapsacks and even on the slippers of the Venkateswara devotees. They saw multitudes of broken pieces of clouds scattered all over the cotton shrubs planted on both sides of the railway track. They longed for the tangy taste of bright oranges they saw at the long orchards near the Nagpur station. They stayed awake that night and waited inside the lavatory for a perfect moment to jump down from the train. When the Kerala Express reached Bhopal Junction, it was two o’clock in the morning. Holding hands, they jumped to the platform, which seemed less crowded. It was November, and the cold wind penetrated their frail form. Aju thought he would faint if he did not drink at least a drop of water. They saw a tap nearby and drank from it. They spent the night on the platform, cuddling with each other on a cement bench at a remote corner of the train station. There were many like them, so no one noticed these two huddled in the corner like two coiled millipedes.

Aju once again saw his mother calling from the other side of the road. This time, there were no blue waves or sharks to engulf him, so he rushed into his mother’s arms. Suddenly, a belt ran across his brown skin, drawing a slanting line from his right shoulder to the left of his hip. Before he could figure out what was happening to him, the rough hands of his father dragged him to the study table and asked him to write the Malayalam aksharamala a hundred times. Malayalam letters like Jilabis appeared before him in different sizes and colours. They appeared and disappeared into the thin air like a fairy twirled her magic wand around them. Tears welled up in Aju’s eyes, flowed endlessly like the crisscrossed Nila and wet the two-line book completely. Once again, the sharks emerged from it, chased him around the big mango tree in front of his home, through the mud road, then through the hot but smoothly tarred, infinitely long State Highway and then through the rocky rail tracks. Tired and startled by the bright flashes of an approaching train, Aju stopped at the railway tracks. Vishnu’s voice brought Aju back to his senses. Vishnu lent Aju a cup of tea. Aju could see Vishnu’s face like an apparition behind the mini steam clouds, like speech bubbles in comic books, rising from the teacup. His smile was like ointment to open wounds. It had the power to bring Aju’s pounding heart to its normal rhythm slowly.

Vishnu had also brought two samosas to feed their starving stomach. When tea and samosa slightly subdued the growling creatures in their tummies, Aju and Vishnu, hand in hand, started walking through the streets of Beegums’s Old Bhopal. They walked carefully without losing each other’s hands among the swarm of unknown faces or dirtying their feet by stepping on the brick-red betel spittle scattered here and there on the road. The roads were not like the village roads in their hometown. It was crowded and unfamiliar. Each face seemed busy, and no one seemed interested in two children walking hand in hand with school bags on their backs. Vishnu remembered the pleasant morning rides through the green paddy fields on his father’s bicycle to buy milk from Raji chechi’s house. Sometimes, Mittu, the two-year-old black and white dog, would follow them. If they are early, they must wait for Meenakshi cow’s daily bathing routine, belly massage, and breakfast—one tub of cattle feed mixed with banana peels—to be over. Only then will she allow Pappan, the milker, to take her milk. Vishnu will carry the milk bottle home, and his father will go to the nearby market to buy other essential items. By then, in his house, breakfast will be ready on the table. Amma will bathe Vishnu properly, dress him in his school uniform, neatly comb his wet hair to the left, and feed him one cup of Meenakshi cow’s milk and puttu, the steamedrice cake made with grounded rice and grated coconut. She will also never forget to put sandalwood paste on his forehead before he leaves for school.

Aju’s daily routine was different. He and his brother Tiju usually wake up by the clanging sounds of steel plates Amma throws into the sink as a response to her displeasure at her unhappy married life. In between the clatter of steel plates, they often hear their grandmother’s voice cursing their mother and the sound of the palm-frond broom over the gravel spread in their wide yard. But, two minutes before their father reaches home from his daily morning walk, all the sounds in the house will stop, and the small clay-tile roofed building will slide into a frightening silence, which seems to have inhabited it for ages. By the time his father reaches the gate, Tiju and Aju will be on the grass lawn, picking up the weeds lurking amidst the expensive grass planted in their yard, which was brought home from one of his drinking buddies’ plant nursery in the town. This was one of the daily duties that their father had given them. After picking up the weeds, they brush their teeth, bathe, have breakfast, and go to school. On Saturdays and Sundays, the duties will be either assisting their father in repairing old mixer grinders, tube lights and other electronic items at home or cleaning the yard. Their father would shout and ask them to come home if they were found anywhere near the playground. Aju and Tiju never disobeyed their father because they knew the consequences their body and mind had to suffer for such an act.

Aju’s fears turned into relief when he saw unknown faces in the streets of Old Bhopal. Vishnu’s excitement had slightly diminished than the first day on the train. Fear and hunger overpowered his little frame. Aju showed him the milk pedas, Bhoondi Laddus and Kaju katlis spread in neat rows, one over the other, inside glass boxes inside small shops. They had their lunch with one green-coloured milk peda each and a small plate of Shahi Tukda. Gaining energy from the sweet delicacies they gulped, they started walking again through the narrow streets of Old Bhopal. By noon, sunlight turned the winter month slightly warm.

The Little Heart and the Little Fish were seeing such a city for the first time in their life. They have only seen Trivandrum City, which has wider lanes adorned with green trees and buildings bearing temple and Victorian architectural styles. Walking through Old Bhopal’s dusty, narrow lanes, their nostrils were filled with smells they could not identify. It was an unfamiliar mixture of cigarette smoke, adrak chai, ripe guavas, freshly cut meat, smouldered veggies, hot seed oil and paan masala. They gazed at the red, grilled chicken pieces hung one by one on slender steel rods in the street shops. Children selling those were almost the same age as Aju and Vishnu. Vishnu licked his lips. Saliva in Aju’s mouth could hold a ship in it. A boy in a dirty white vest gave them two pieces on a paper plate and smiled. Aju and Vishnu smiled at him and accepted his offerings. When Aju looked back at the boy, he saw a glowing halo around his smiling face.

Munching the hot glazing chicken, Vishnu and Aju wandered through the allies. Suddenly, Aju’s eyes caught on several small triangles flying so high in the sky through the top of the dusty buildings in the lane. Like the Magus who followed the star of Bethlehem, Aju followed the coloured triangles he saw in the Bhopali winter sky and dragged Vishnu along with him. At last, they found the origin of those tiny triangles at the thousand steps of a massive pink building with three white domes facing the sun and two tall minarets touching the sky. Aju and Vishnu gaped at the Mughal architectural marvel for a minute.

Vishnu said, “Aju, we reached Agra. See, this is the Taj Mahal”

Aju looked at Vishnu and said, “But this is pink. The Taj Mahal is white. I have seen Taj Mahal’s photo on last year’s calendar. This looks a bit different.”

“It is old. It may have turned pink.” Vishnu said.

Let’s ask those boys flying the kites. Aju said.

They approached the boys, who were enjoying the kite fighting.

Aju asked one of the boys in Malayalam, “chetta, ith Taj Mahal ano? Is this the Taj Mahal?”

The boy looked at him and responded. “Kya??”

Puzzled, Aju looked at Vishnu and reiterated, “Kya…?… Hindi … Hindi. Do you know Hindi?”

“Yes, Thoda Thoda Malum”. Let’s see Leela teacher’s Hindi classes were of any use. Vishnu said.

Vishnu then asked in a South Indian accent, “Ye Taj Mahal hai?”

Aree… buddhu… Ye Taj Mahal Nahi. Ye hai Taj-ul-Masajid. The boy said and turned to see whether somebody had cut his kite down.

Vishnu again interrupted and asked him, Ye place, Agra he na?

Aree…chuchundar, ye Bhopal hai….

Like the people on the street, the boys flying kites also showed no interest in two tiny South Indian boys standing in front of the enormous pink façade of Taj-Ul-Masajid built by Shah Jahan Begum and Sultan Jahan Begum of Bhopal. After watching the winter sky adorned with different coloured kites, Aju and Vishnu entered the Masjid. There were several wazukhanas inside the sahn or the wide courtyard. Both of them were entering such a building for the first time. They washed themselves up in one of the wazukhanas. With trembling feet and astonished hearts, they looked at the impressive Mughal architecture of the Masajid. The aura of Taj-Ul-Masajid was mesmerising, and its name literally reflected its meaning as the crown of mosques. Aju felt like they had time-travelled a few centuries back in history. They forgot themselves while gazing at the red sandstone structure and chandeliers.

Suddenly, a hand touched Vishnu’s shoulder—a huge man with grey bread and a white taqiyah. Aju’s relief at the strangeness surrounding him was slightly shaken by the sharp gaze of the man. He was reminded of his father. He wanted to run away, but Vishnu seemed hypnotised and looked back at the colossal figure. A growl escaped Vishnu’s stomach. As if in a trance, Vishnu said to the man rubbing his empty belly, “vishakkanu”. I am hungry.

“Bhukh lagi hai? Aao… kuch doonga.” Hungry? Come, I will give you something.

Like the rats followed the pied piper of Hamelin, Vishnu and Aju followed the man to the nearby room constructed for the students of Darul Uloom. He opened the door. It was a small room with one small bed, a table and a chair. In the corner of the room, there was a small pot full of water. He took two apples from a plastic cover placed on the table and gave one to Aju and one to Vishnu. At that point, this man turned out to be the kindest man they ever saw in their journey after the boy with a halo who gave them chicken kababs.

Gently, the man asked Vishnu and Aju, “Kya aap Madras se hai?” Are you from the South?

Vishnu said, “Madras nahi, Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram”. Not from Madras, from Kerala. “Apka koyi hai idar?” The man asked them again. Aju and Vishnu looked at each other.

Then man said to Vishnu, “aapne papa ka number do. Me call karunga…” Give me your father’s number. I will call.

Puzzled, Vishunu and Aju exchanged glances. With his sweetest voice, with which he usually says azan, the man asked Vishnu, “Number… phone number… papa ka…” Without a second thought, Vishnu gave him the number and told him his father’s name was Prasad. Aju stared at him furiously. Vishnu then said, “Enik pattunnillada. Namuk thirich pokam”. “I can’t take this anymore, buddy. Let’s go back home”.

The man showed his tiny bed to them and asked them to take some rest. The bed was enough for the Little Heart and the Little Fish. They were so tired they slept cuddling with each other like they had the first time at the railway station. This time, at their houses, their mothers were wailing inconsolably. Relatives and neighbours had already searched all the ponds and wells in their neighbourhood. There were rumours that somebody had seen a group of nomads in their region on the same day of the children’s disappearance. Aju’s mother vented out at her husband, the decades of anger and remorse that settled in her heart. The steel plates were happy that day because Aju’s mother was not in the mood to throw them into the sink like she did every other day. She even blamed him for Aju’s missing and declared that Aju would not come back until he heard about the death of his father. Aju’s father sat in the easy chair, unable to take the guilt of the sins he had committed against his wife and sons over the past few decades. Tears rolled down his cheeks without sobs or sighs. It flowed like the crisscrossed Nila his son crossed to escape his belt. It cost him years and one son to realise the damage he had done to his own family. The silence that inhabited the house seemed unbearable to him for the first time.

At Vishnu’s house, the entire neighbourhood had gathered to console Vishnu’s father and mother. They did not cook anything at their house since the child went missing. His father searched all day and night at the nearby bus stops, railway stations and hospitals. He did not go to buy milk from Raji chechi’s house. Vishnu’s mother was on the verge of collapse when the phone rang. One of the neighbours took the phone. The only thing he understood was that the call was from Bhopal. “Hindi ariyavunna aarelum undo?” Does anyone know Hindi here? People looked at each other. One person ran to call Leela teacher. Leela teacher came and spoke to the man who had called from Bhopal. Slowly placing the receiver on the landline, Leela teacher said toVishnu’s father, “vishamikkenda. Piller safe aanu. Avar Bhopalil und”. Don’t worry. Children are safe. They are in Bhopal. She shared the address that the man gave her.

Mr. Sayyed Mohammed

Taj-Ul-Masajid

National Highway 12

Kohefiza, Bhopal

Madhya Pradesh, 462001.

The next morning, Prasad and Mathew boarded the same Kerala Express 12626 their sons had boarded four days ago. It seemed like the silence that was brooding in his house had now transferred its abode to Mathew’s body. Prasad seemed a bit relaxed since he understood that Vishnu was alive. They crossed Nila without looking at its crisscross form. They neither saw pieces of clouds scattered among the cotton plants on the sides of the railway tracks nor tangy oranges in Nagpur, even though they looked out through the windows throughout their journey. Mathew was rewinding the life he wasted without loving his children. At times, sighs escaped his chest with the disappointment in making his life and the people’s lives around him so miserable with his ego. Meanwhile, Prasad was trying to figure out where he had failed as a father. Thoughts rumbled through their minds as the train carried them from Trivandrum, the city of seven hills, to Bhopal, the city of lakes.

Two days later, when they arrived at the Masajid, Vishnu and Aju were playing hide and seek around the minarets and the corridors of the pink Masajid. They looked happy but thin and tired. When Vishnu saw his father, he ran into his arms and cried in joy. Aju stood where he was standing and gazed at Mathew. Mathew could not control his emotions this time and wept like a child. Tears ejected decades of unhappiness, lovelessness, ego and filth that settled inside him for years. Aju slowly came to his father and touched his shoulder. Mathew embraced his son and kissed his forehead several times. Mathew and Aju stood in that embrace for a few minutes. Prasad and Vishnu looked at Aju and Mathew and smiled. Masajid’s white dome glittered in the twilight. The minarets reflected its pink face in the calm waters of the wazukhanas. Sayyed’s sweetest voice, saying azan, was heard from the loudspeakers tied to the minarets of the Masajid. It floated through the air and surrounded all the four who were already embraced by the warm twilight of the evening sky.

Glossary

Nila – also known as Barathapuzha or Ponnani River, is a river that flows through Kerala and Tamil Nadu

Erode – city in Tamil Nadu

Idli-vada – a South Indian dish made of rice and urad dal

Tirupati – City in Andra Pradesh

Venkateshwara Temple – A temple in Tirumala Andra Pradesh dedicated to Venkateshwara, a form of Vishnu

Puttu – a dish made with grounded rice and grated coconut

Dothi – also known as mundu or veshti, is a loincloth worn by Indian men

Aksharamala – Alphabet or system of letters

Jilebi – a sweet dish usually made in India

Beegums of Bhopal – four women rulers—Quadisa Begum, Sikander Beegum, Shah Jahan Beegum, and Sultan Jahan Beegum—ruled over the princely state of Bhopal from 1819 to 1926.

Old Bhopal -Certain parts of Bhopal city, such as Peer Gate, Gauhar Mahal, Sadar Manzil, etc., which retain the old buildings of Nawabi architecture, are defined as Old Bhopal.

Milk pedas– anIndian confectionary made of milk solids, sugar and ghee.

Bhoondi Laddus – Indian confectionary made with gram flour, sugar and ghee

Kaju katlis -Indian confectionary made with Sugar and cashews

Shahi Tukda – Indian bread pudding made from fried bread slices soaked in sugar syrup. It is believed to have originated during the Mughal period.

Adrak chai – Ginger tea

Chechi – elder sister, also used to refer to any female older than the speaker

Taj-Ul-Masajid – the largest mosque in India, situated in Bhopal.

Wazukhanas – a pool in front of a mosque to perform ablution before prayer.

Darul Uloom – can be translated as “house of knowledge”, refers to Madrassa, the Islamic educational institutions.

Sahn – Courtyard of a mosque

Taqiyah – cap worn by Muslim men

Azan – Islamic call to prayer

Anu Susan Abraham is a doctoral research scholar in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IISER Bhopal. From “Trivandrum Cntrl. to Bhopal Jn.” is her second short story. Her first short story, “Death of a Lady”, was published in Creative Flight Journal in

2023.

Travels With Henry by Martha Ellen

Henry loved cars. They were his alter ego and his escape plan.

1. There was only one chick magnet.

Finally, in 1998, Henry had the chick magnet he always wanted, a black 5.0 liter Mustang GT. All the cool guys in 1952 had hotrods. They got all the angora-sweater-wearing bobby-soxers.

Making the turn south from E. Harbor onto 101, he sped up and “peeled out”, sure to impress, Addie, his son’s girlfriend riding behind in their brown ’85 Volvo station wagon that served to transport Nick’s double bass to gigs. Cool cat. The old bag sitting in the passenger seat of the hotrod knitting baby clothes for their grandchild, ruined everything. He traded in the old hotrod for a newer model.

2. There were two dream cars.

The 1971 factory-issue blue and white VW bus he had repainted bright yellow, with a red stripe. The painter from Warrenton called. He couldn’t bring himself to paint the wheels black as Henry wanted. “It’s gonna look like a toy.” Henry planned to install a small wood stove inside. Internal combustion engine be damned. Then he would affix a faux periscope on top of his Yellow Submarine but he rolled it on Highway 26 one Winter day. Hip. The last time I saw it was in a junk yard on 101 just south of Seaside.

One Christmas morning in 1980 he ran to the front picture window and looked toward the driveway in eager anticipation. He was still in his skivvies and t-shirt. He had been eagerly awaiting daybreak. Crestfallen. Disappointed. The black Porsche with a big red bow was not there. He thought for sure I had plotted in secret to surprise him on Christmas morning. “You called ten people who love me and told each you wanted to surprise me with a new Porsche.” I asked, “Can you send $1000?” They thought it was a great idea and sent the money without hesitation. He had drawn up a list of the ten people that included his sister. “Your sister hates you.”

Where would I have found a big enough bow anyway?

3. And there were three get-away cars.

On a cold late Autumn day in 1968 in northern Illinois he drove me to the LaBagh Woods in his 1965 green and white VW micro bus. No one would be there so late in the season. I was pregnant. I followed him on an uphill footpath to a secluded area. He turned abruptly and looked directly at me. He hesitated. Then he insisted we leave. We weren’t in the forest preserve to commune with nature, Hippie style, as I believed. He was checking out the feasibility of a plan I knew nothing about until much later. He would escape racing east to Detroit and cross the border to Windsor. Home free. He sold the bus for $500.

In 1982 there was another plan to escape to Canada. He marked the back road on the Rand McNally map with arrows pointing the correct direction, North, in case he forgot. As he raced his 1978 yellow and white GMC van as fast as it would go, the police chasing after him fired guns at the van trying to blow out the tires, he would flip the magic switch on the dash. The metal plates he had installed in each wheel well, a Rube Goldberg contraption involving hydraulics and fishing line, would drop down and deflect all the bullets. I could almost hear the banjo soundtrack. “They will probably put down spike strips.” Later I wondered what event, real or imagined, had triggered the fantasy. The missing girl from Astoria came to mind but I had no solid evidence. He sold the van for $800.

In 2020, among other items he left behind, I found the owner’s manual to his 1955 British green Austin-Healy. A souvenir. I opened it. A yellowed page fell out. It was his story from 1955. He drove Maria to Tijuana to dump her off with family. She was pregnant. Casate! Casate! Her demands fell on deaf ears. He crossed the border and sped north to Santa Ana. The Highway patrol stopped him on a BOLO for a guy matching his description driving the same car. They let him go. Close call. He ditched the sports car on a back road. I couldn’t breathe. I finally understood the LaBagh woods when he didn’t want to press his luck.

Martha Ellen lives alone in an old Victorian house on a hill on the Oregon coast. Retired social worker. History of social justice activism. MFA. Poems and prose published in various journals and online forums. She writes to process her wild life.

What the Witch of Lambs Lane Taught Me by Cesca Waterfield

I was seven years old the first time the mother next door screamed that I was a witch as she sped away in her car, showering my spindly legs with gravel.

I heard the chug of her Buick before I saw it. As my school bus lumbered away, Darlene turned off the state road, muffler belching fumes like a smoke machine on American Bandstand. Though I hadn’t met her, she waited each weekday at the end of her woods-shrouded driveway to collect her teen girls, the heavily eye-shadowed bullies Tanya and Tammi.

I made my way down Lambs Lane as Darlene caught up and stopped alongside me. From behind the wheel, she called through the open passenger window, “Wanna ride?” Tanya’s eyes crinkled in glee, lashes caked with mascara. Her cracked lips curled in a smile above her braces. Darlene fixed her brown eyes on me and turned down the radio. “I hear somebody has a birthday coming up.”

I shifted my weight to my other foot. My gut tightened. “It’s not for a few months.” She raised her eyes to the rearview mirror to look at Tammi and said, “Well that’s comin’ up, ain’t it?” She tapped the steering wheel. “Do you want what we got you or not?”

Where I came from, grown-ups were to be obeyed. No questions. No hesitation. Especially a neighbor. It was eight months since we’d moved to this small town in Virginia from a suburb in Alabama. There, grown-ups kept order, corrected me often enough, and showed kindness. They were the ones to find if you skinned your knee at the playground or got lost, or found yourself in an emergency.

I walked around the hood of the car to the door and reached for the chrome handle with sweaty fingers. Suddenly the car lurched forward as Darlene gunned the engine to the chaw of gravel. Her sharp chin reflected in the side mirror as she hollered, “We don’t give rides to little baby witches!” High-pitched laughter flickered above the muffler’s chugga chug. The car turned by the End of State Maintenance sign and raced past me in the other direction. “Your family loves the devil and your mama’s a witch! That’s why there ain’t no windows on the side of your house!”

My shins stung from gravel her tires had spun up. My heart pounded as I held my breath against the musty fumes. This town felt like an amusement park ride, a dodgem car. It had turned everything I knew upside down. Life in a storm of heat lightning–silent, but looking out at a world inverted like a photo negative. I snatched a handful of wood sorrel from the roadside. At home in the kitchen I put the heart-shaped leaves and tiny flowers in a glass, filled it with water, and stared at the humble display. Darlene’s shrieks echoed in time with my racing heartbeat. On a hill often rocked by river winds, the contractor who’d built our house designed it so it didn’t have windows on the north wall. My father agreed and one side of our house was all brick.

But how could someone so hateful call my mother or me a witch when her own daughters tormented children on the bus? How could I ever fit in where cruelty was a yardstick for survival and my mother, whose baby fine hair lifted as she played with her students at the playground could be called a witch?

I got on my bike and pedaled away from where Darlene and her girls had left me standing. I rode fast, as if speed itself could peel their words off me. But even as I pedaled away, I still bore the mark of what had happened. The gravel that slung out from Darlene’s tires was settling back into place, as if nothing had disturbed it. The air still held the ghost of their laughter, tangled with the scent of exhaust.

Yet, along the edges of the cracked asphalt, tendrils of hope in the persistence of weeds. Out here, where fields stretched to the river and pinewoods crowded the roadsides, the rhythms of nature intertwined with daily life. Endurance wasn’t just a matter of necessity—it was often an act of defiance, mirrored in the land. In town, flowers could spring up in the sidewalk cracks. But where we lived was so far out, weeds and flowers grew in the road. Even with fields planted and harvested year round, tractors, combines, and trucks didn’t number enough to abrade aspiring seedlings, and when asphalt cracked in steam-humid summers and winters that could bring blizzards or dump record hail, it opened up to seeds that set down and shivered in the hot breath of spring. Gumweed, corn speedwell, crabgrass, pigweed, and dandelions grew against all odds, forever stronger and more determined than a brigade pillaging at dawn. I rode so furiously, my banana seat began to sigh like the spinning reel of a fishing pole cast hungry out into the river.

But the shag arms of quackgrass waved, sprigs that looked like square root symbols in the algebra textbook I’d kicked under my pink ruffled bed skirt. They stood and waved in the heat, not as surrender, but as defiance as I pedaled past, sweating, legs pumping my body forward over their flourishing. As I cooled off up to my ankles at the wharf flooded in high tide, I understood: the road wasn’t just something you traveled—it broke open and made room for whatever had the will to push through. My model for living was out there, forever standing, roots deep and dug into the fractures.

Cesca Waterfield grew up in Alabama and Virginia in the U.S., where she fell in love with the music of cicadas and the lilt of regional accents. Her work has appeared in The Comstock Review, Scalawag Magazine, Mystery Tribune, LUMINA, and more, and she is the author of poetry collections The Oyster Garden and Conspiracy Cherry.

How I Experience the Uzan Bazar Area, Guwahati. by Shruti Sareen

My dreams in Delhi at night are of traversing the river road and the Latasil quadrangle. In my dream, i have got a dream-ticket back there again. I woke up telling myself that stepping out of my Delhi house is of no use because the river road and the Latasil quadrangle are not out here.

Each one of us builds our own different connections with different places in many different ways. According to LeFebvre, there are lived spaces and there are social spaces. I have limited knowledge of the social spaces of Uzan bazar, i understand both the scheduled castes and the upper caste ‘brahmins’ live in this locality, and you can tell the caste by knowing the sub-area within the locality wherein the person lives. This place is teeming with histories i do not have much idea about. I know this is the oldest city square in Guwahati from where the city began, way before the encroachment of the malls and the high rises. Lived spaces, writes Lefebvre, are our personal associations and memories with places in our heads. But i have no personal memories in this place. Isn’t it strange, how much i have imaginatively connected with it in my head, just knowing this is the place where you grew up? You, who have not spoken to me for nearly 20 years now.

When i first chanced upon the river road of Uzan Bazar in November 2023 in search of Belle view point, it was a near total surprise to find this beautifully quiet road overlooking the river right next to the bustling marketplace. Did you not write that your house overlooked the river? Did your sister not write that your house was in Uzan bazar? So then, right here, Uzan bazar river road, could your house possibly be here? I looked at all the small apartment buildings on the road, imagining which might be yours. Railway colony– no probably not. Tiny fisherman’s colony with the fish market– perhaps your ancestors lived in such a place. And suddenly the incredibly posh krishnamoyee apartments on McCall road just round the corner. Smart house with posh garden on river road– no, probably your house was not so posh. I imagined it to be a modest middling apartment– not too posh, yet not in the throes of poverty. Was it one of the apartments on the river road, or one of the apartment clusters slightly further away from the river road? MG road, but in my mind, it was alternatively the river road and your house road. In February 2024, I made it mine by staying for a night in Riverview guest house. This time I stayed in Blue Moon, last time in that shady Kobitaloi due to prices. Riverview apartments were there, Urvashi apartments right next to it. By now, the novelty was wearing away. I walked the length of the road, watching Umananda island and the long and narrow island. These are populated densely with trees, unlike the other sandy islands, especially up nearer the governor’s house on the other side of the road– sandy islands and the palm trees– the picturesque scene so resembled a sea scene! The road was dotted with tiny tea shops, cafes, little temples and even a ‘marriage bureau’! Cafe Bellevue, October Cafe, TLC 7 cafe. I had tea in one of the little tea shops with my student Diptiman, and also ate alone. And that lovely favourite banana cake. But the construction for the flyover has spoilt the river view now, I tried to imagine how lovely it would have looked without the construction– the way you would have grown up! How places continuously change under the onslaught of time. Riverview guesthouse is still charging extra for the river view even when there is no view anymore. I also saw some chicks being transported in two baskets. One basket to keep the chicks in, the other to cover. Being a vegetarian, perhaps this sight was a little disconcerting for me to see. But I just accepted it as part of the landscape. The alterity of the other. Of course, I had sometimes seen such scenes in other cities too—Delhi, and Varanasi where I grew up. There I used to see big scale transportation with loads of chicks stuffed in a van. Here, it was so small scale, just two baskets. How differently each of us experiences any scene, any place! However, I was uneasily aware all along how my actions could be seen as stalkerish, haunting the childhood home locality of your teacher because you fell in unrequited lifelong queer autistic oedipal love with her, nearly 2 decades after she stopped speaking to you. Taking photographs was the maximum extent of my stalkerishness, although I think I had an idea of your parents’ names, I was overwhelmed by the enormity of an act like asking random people such questions. I preferred to let my imagination reign.

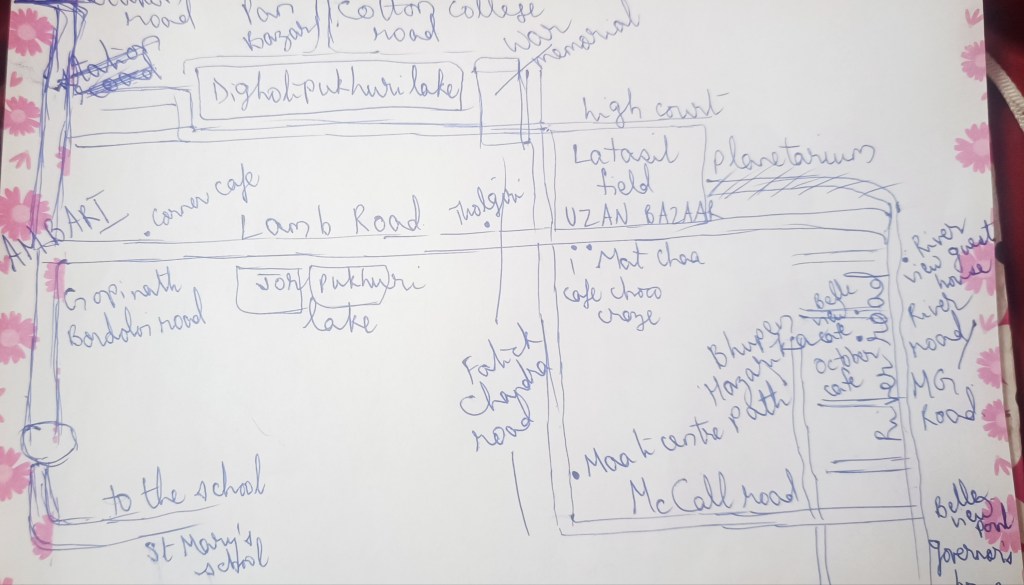

It was only in February 2024 while taking the turn from the river road that I realised it was so close to Latasil! Latasil which I had read about in all my stalkerish endeavours. Lota-xil—creeper and stone, my friend Stuti told me. I have fallen in love with this area. Entering the Latasil quadrangle from the planetarium side, coming from the river road, the high court to its other side. The same MG river road turning into Latasil, going right past it, becoming the cobbled Lamb Road, leading past the quaint little Tholgiri where I relished Assamese food to my heart’s content, and Qalaa, the Corner Cafe and other shops, right to Ambari! When I asked in Qalaa if they are the best bakery in the area, they proudly replied they are the best bakery in entire Guwahati. The ugratara temple nearby. So Lamb Road connects Uzan Bazar to Ambari, the main road with state museums and emporiums. Your school is still 500metres from here, beyond the roundabout– quite a long way for a small child to walk from the river road, I thought. You said you walked to school, didn’t you? And before we get to your school, there’s Pragjyotika, the assam emporium, chock full of ethnic curiosities from assam and all over north-east. I am a frequent visitor to the Delhi Pragjyotika, but then visiting Pragjyotika in Assam is another experience. Then back to Latasil, Lamb road cuts across Fatick Chandra road. See, Choco craze cafe and Mat Chaa! High court, planetarium, Lamb Road, Fatick Chandra road around the Latasil field where boys play cricket. On the Lamb road, I crossed by those two little ponds, Jorpukhuri. I saw ducks and geese and water birds there– did you see these on your way to school every day? Google maps helped me a lot. It also helps me fill the gaps in my knowledge. I walked and walked. Come to fatick chandra road. Go down one way and you come to the lovely little Maati Centre from where I bought so many pickles and teas and handicrafts, and sweets from Tholgiri. Finding walking with my heavy shopping bags a little difficult, I thought to myself that it would take time to go back home and keep the bags. I surprised myself. I realised by ‘home’, I was referring to the Riverview Guest House. I had already checked out by then. Was it your home, or was it mine? This is how it begins to get fuzzy, you see. A little way down FC Road beyond Maati Centre, and it turns into Mc Call road, leading right back to the river road. Cutting across Mc Callroad is Bhupen Hazarika Path, my friend Rajashree lives there in Kharghuli. I have stayed over at Rajashree’s place when i have visited here earlier. See, how close Rajashree’s house is to your house– bhupen hazarika path runs parallel to the river road, and both are connected by Mc Call Road! Never before have I turned detective like this– never before have I paid so much interest in roads and directions. But this place fascinates me. I am obsessed. Okay, back to Latasil, let’s go down the other way on Fatick Chandra road now. I have even done the most mundane things on these roads, you know, medicine shops, printer shops, emergency charger shops. Falling down dead and searching for some decent place where I can fall down awhile and have a bite to recoup. And we come to Dighalipukhuri! Straight down FC road and you have the front of the high court on your right and the war memorial on your left. But turn left and you find yourself walking down the loveliest road you ever saw, lined with the loveliest of trees, and the artificial lake, Digholipukhuri, running all down the road. When i first saw this road in 2014, i thought this was the river! I was aghast and horrified at learning that the antique and gnarled trees down the Digholipukhuri road are to be cut down. I wrote a poem on it too. Thankfully others too thought like me and protested, and the disaster was averted.

This road will again lead you to Ambari so it must run parallel to the Lamb Road. Ah, me the detective! Take the turn round Digholipukhuri lake and Rajashree says this is the khao gali, lined with streetfood carts. If you take the turn from here to the intersecting perpendicular road, that’s the station road and you get to the railway station here. But stay with me a while and walk around Digholipukhuri, so war memorial opposite khao gali, the two shorter sides of digholipukhuri rectangle, and then that lovely long road on one side and another similarly lovely long road on the opposite side of Digholipukhuri– you take the perpendicular road and you come to Cotton College/University, Pan Bazar! I imagine you walking to school and to college everyday. You see how I turned detective, and how google maps helped me with the pieces of the jigsaw! Walking down the Cotton College road, beyond the intersection is Nedfi, the wonderful store for North-Eastern handicrafts. Writing about all my wonderful handicraft and food experiences and discoveries, many of which I hoard and bring back with me to Delhi, is unfortunately beyond the scope of this little piece.

There’s so much more to explore and so many gaps in my map that need to be filled and detailed. I think you would mind it, though. You would mind me walking over all these paths and lanes, so well-known to you. I understand it can seem like an invasion. And yet how do I explain to you the beauty, the joy, the calm serenity I get from being in this place, overwhelmed by trying to connect with you in my imagination, this place where I walked and walked, like you did decades ago, where words like “sukh” and “tripti” and “poorti” come to my tongue spontaneously, hindi words for fulfillment, satisfaction and contentment? I want to come here again. And again. Yet I do not want to hurt you. It becomes a life and death dilemma for me. Can you understand? The flyover on the uzan bazaar river road will get built, but will this bridge ever be, I wonder?

I have the germs of a fantasy novel in my head. Part of the setting for this novel will be on Saturn, and the other part on an imaginary island, right in the middle of the Brahmaputra, right next to the Uzan Bazar river road. I was reading more about the area and have even applied for a research project on it! So I learnt a bit more about place names and histories. How can I write it all here! Does Uzan mean upstream? Did people here migrate from upper Assam? A girl once told me you are originally from Sibsagar. I don’t know.

Those were my initial wanderings. Now that I repeatedly return to my favourite area on the pretext of interviews and conferences, many people in the aforementioned shops and restaurants like Maati Centre, Tholgiri and Nedfi recognise me, welcome me. They know me, my interest, and my fascination. It’s a little over a year since my initial wanderings, and see, how many times I have visited, and how much I have transformed it into my home already! I hope Blue Moon Hotel sees me much oftener than once in a blue moon. I am making the area mine, recreating it, owning it. Having been bereft and dispossessed of previous homes, I am learning to call your home, my home.

(NB: a crude, inaccurate, hand-drawn map follows, with so much more to explore, and so many gaps in my map that need to be filled.)

Shruti Sareen has a PhD in English literature from Delhi University and teaches in

colleges/universities whenever she manages to find a job. Her poetry collection, A Witch

Like You, appeared in 2021. She has a fictional memoir on the verge of publication and is

engaged in writing speculative fiction, love-letters, and of course, more poetry!

Leave a comment